London Protocol (1830)

| |

| Context | The first official international diplomatic act that recognized Greece as a sovereign and independent state. |

|---|---|

| Signed | 3 February 1830 |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Parties | |

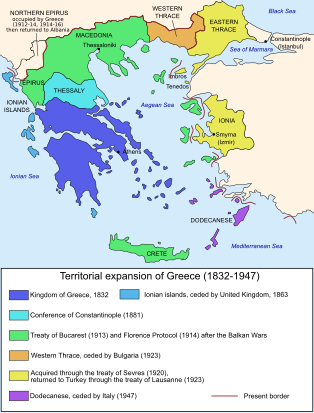

The London Protocol of 1830, also known as the Protocol of Independence (Greek: Πρωτόκολλο της Ανεξαρτησίας) in Greek historiography, was a treaty signed between France, Russia, and Great Britain on 3 February 1830. It was the first official international diplomatic act that recognized Greece as a fully sovereign and independent state, separate from the Ottoman Empire. The protocol afforded Greece the political, administrative, and commercial rights of an independent state, and defined the northern border of Greece from the mouth of the Achelous or Aspropotamos river to the mouth of the Spercheios river (Aspropotamos–Spercheios line). As a result of the Greek War of Independence, which had broken out in 1821, the autonomy of Greece in one form or another had been recognized already since 1826, and a provisional Greek government under Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias existed, but the conditions of the Greek autonomy, its political status, and the borders of the new Greek state, were being debated between the Great Powers, the Greeks, and the Ottoman government.

The London Protocol determined that the Greek state would be a monarchy, ruled by the "Ruler Sovereign of Greece". The signatories to the protocol initially selected Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha as monarch. After Leopold declined the offer of the Greek throne,[1] a meeting of the powers at the London conference of 1832 named the 17-year-old Prince Otto of Bavaria as the King of Greece and designated the new state the Kingdom of Greece.

Background

[edit]From George Canning to the Battle of Navarino

[edit]The Greek War of Independence began in 1821, and by January 1822 the provisional government of Greece had established an assembly, and a formal constitution.[2] By 1823, the British Foreign Secretary George Canning was taking an keen interest in the 'Greek issue'. He wished to see the international recognition of Greece, in order to impede Russia's expansion into the Aegean Sea.[3][4]

- January 1824: Russia proposed a plan to create three principalities, following the model of the Danubian Principalities: Eastern Greece, Epirus and Aetolia-Acarnania, Peloponnese and Crete. This plan did not satisfy the Greeks, who were fighting for independence.[5]

- June 1825: Act of Submission: Under pressure from Ibrahim Pasha's victories in the Peloponnese, the Koundouriotis government asked the British government to choose a monarch for Greece, stating its preference for Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. With this act, they essentially asked for Greece to become a British protectorate. Canning, however, refused to accept the act.[6]

- April 1826: The Protocol of St. Petersburg was signed jointly between Britain and Russia. This was the first text that recognized the political existence of Greece, and it provided autonomy to the Greeks.[7]

The terms of the St. Petersburg protocol were repeated in the Treaty of London in July 1827. This treaty set out to cease hostilities in Greece, and proposed that Greece become a dependency of the Ottoman Empire, and pay a tribute to reflect that. Later amendments gave Turkey one month to accept. A secret "supplementary" article also provided for military coercion, on both sides, to force acceptance of the terms of the Treaty.[8] This eventually led to the Battle of Navarino (7/20 October 1827). The defeat of the Turkish fleet by the three Great Powers (Great Britain, France, Russia) gave hope to the Greeks, although the European powers still only spoke of autonomy, rather than independence.

Change of British policy and delineation of the Greek borders

[edit]From 1827 to 1828, there were major personnel changes in the British government. George Canning was promoted from Foreign Secretary to Prime Minister in April 1827; but died in August after just 119 days in post. Viscount Goderich followed as Prime Minister, but only until January 1828, when he was succeeded by the Duke of Wellington. Canning was succeeded as Foreign Secretary first by the Viscount Dudley and Ward and then in June 1828 by Lord Aberdeen.

- 11/23 September 1828: Ioannis Kapodistrias, Governor of Greece, sent a confidential memorandum to the three powers, protesting against the limited borders of the new state, which he foresaw would be proposed by their representatives. He avoided raising the issue of independence.[9]

- November 1828: The British Foreign Secretary, Lord Aberdeen[10] recommended the first London protocol be signed on 4/16 November with unfavorable terms for Greece: only the Peloponnese and the Cyclades were granted to Greece. This provoked a strong reaction from Kapodistrias.[11]

- March 1829: Disputes among the three Powers were exploited by Kapodistrias, and led to new negotiations and the second London protocol. This protocol of 10/22 March 1829 proposed the following:

- a. A border from the Ambracian Gulf to the Pagasetic Gulf, including the islands of Euboea and the Cyclades in the new state.[12][13][14]

- b. Sovereignty of the Sublime Porte over the Greek state with an annual tribute of 1,500,000 kuruş payable to the Sultan.

- c. A Christian and hereditary ruler of Greece, not from the royal families of the three Powers, who would be elected "by the consent of the three Courts and the Ottoman Porte".[15]

Russo-Turkish War (1828-1829) and Treaty of Adrianople

[edit]The Ninth Russo-Turkish War ended with the defeat of Turkey in 1829, Russia forced Turkey to sign the Treaty of Adrianople (14 September 1829).[16][17] The Treaty of Adrianople gave the Ottoman Empire suzerain rule over the Danubian Principalities of Moldova and Wallachia, and permitted Russia to take control of the towns of Anapa and Poti in the Caucasus, and placed Russian traders in Turkey under the jurisdiction of the Russian Ambassador.

Another change of British policy and the proposal of independence

[edit]Once Russia emerged victorious from the Russo-Turkish War, Russia sought to resolve Greece's wish to become a sovereign nation. Russia forced the Sultan to agree to grant autonomy to Greece and accept terms over Eastern Mediterranean trade that were favourable to Russia. Britain, who was involved in helping the other Powers liberate Greece, had their own terms as well. The purpose of the British policy was to create an independent Greek state that would close routes to Russia in the Aegean and reduce Russian influence in the newly formed Greek state. At the same time, however, they sought to limit the borders, especially in Western Greece, so that there would be a safe distance between the new state and the Ionian Islands, which were then under British occupation.[18] The Greek government asked the Powers that the northern border be changed to include Mount Ossa but the Powers responded that this was not possible.[19] Thus, a new round of negotiations were commenced, which resulted in the protocol of independence, or the London protocol of 1830, signed on (22 January / 3 February 1830).

Participants

[edit]The plenipotentiaries of England, France and Russia (Lord Aberdeen, Montmorency-Laval, Leuven) participated in the London negotiations and signed the protocol of independence, while representatives of the Greeks and Turks were absent. All three countries aimed to increase their influence in the newly formed state while limiting the influence of their opponents. Kapodistrias was excluded from the negotiations due to British suspicions that he was inciting a revolution in the Ionian Islands.[20] In response, he warned that he would not accept unfavorable terms for Greece and insisted on his country's right to express itself at the Conference.[21] The Sultan of the Ottoman Empire had agreed to sign everything that would be decided at the London conference, in order to end the war.[22][23]

Signing of the protocol

[edit]The 11 articles of the protocol,[24][25] recognised an independent Greek state with a border along on the Aspropotamos–Spercheios line. Initially, Euboea the Cyclades and the Sporades were adjudged as part of Greece, while Crete and Samos were not. In a second protocol on the same day Leopold was elected as the "Ruler Sovereign of Greece”[26] and a loan was granted for the maintenance of the army that he would bring with him.[27] The Great Powers demanded that Greece respect the life and property of Muslims in Greek territory and withdraw Greek troops from the areas outside its borders. With the protocol of 3 February, the war ended, and the Greek state was formally recognized internationally. The recognition of Greece by the three powers and Turkey is a critical turning point in Modern Greek history. However, these decisions were not final in terms of either the borders, or the sovereign. These aspects were settled later, with the international acts of 1832.

Kapodistrias's reactions and actions to improve the northern borders

[edit]On 27 March / 8 April 1830, ambassadors from Russia, Britain and France notified Greece and the Ottoman Empire of the protocol.[19] The Sultan accepted the independence of Greece. Ioannis Kapodistrias, who had once been the Foreign Minister of Russia and was now the first governor of Greece[28] agreed with the condition that Turks evacuate Attica and the island of Euboea.[29] He also requested support to help with the expected influx of Greek refugees from outside the borders. He also informed Leopold, who was made king of Greece, about his claims,[30] and asked Leopold to embrace Eastern Orthodoxy, grant political rights to the Greeks, and work to expand the borders in order to include Acarnania, Crete, Samos, and Psara.[31] When Leopold's request for funds to put the Greek finances onto a stable footing was refused by the British government, and seeing the scale of the challenge ahead, he resigned.[32] Leopold argued that he did not want to impose the unfavourable decisions of foreigners on the Greek people; [30][33] but he also resigned for personal reasons.[30]

Inside Greece, opposition politicians were relatively satisfied with the terms of the protocol, but accused Kapodistrias of failing to get a border solution that suited Greece, rather than Britain and Russia.[34] As governor, Kapodistrias attempted to establish central governance over Greece. He also organised tax authorities, sorted out the judiciary, and introduced a quarantine system to deal with typhoid fever, cholera and dysentery. However, his government became increasingly unpopular.[28]

After the protocol of independence

[edit]Leopold’s resignation, and Kapodistrias’ postponement policy led to a new conference in July 1831, with a proposal to extend the border to the Ambracian Gulf - Pagasetic Gulf line. Turkey was forced to accept these terms and a new protocol was finally signed on 14/26 September 1831. However just days later on 27 September / 9 October 1831 Kapodistrias was assassinated.[35] He was killed by Konstantis and Georgios Mavromichalis after Kapodistrias had ordered the imprisonment of senator Petrobey Mavromichalis.

After Kapodistrias' assassination,[36] Russia, Britain and France met in the London conference, and confirmed in the Treaty of Constantinople that Prince Otto of Bavaria would be made King of Greece.[37][28] This treaty finally provided for the independence of Greece, and the enlarged Pagasetic Gulf - Ambracian Gulf border.[38] Prince Otto, newly crowned, arrived with a Regency Council in Greece in 1833.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 575.

- ^ "3 February 1830: Greece becomes a state". www.greeknewsagenda.gr. 3 February 2021.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 313.

- ^ "George Canning | Walking with the Philhellenes". www.walkingwiththephilhellenes.gr.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 371.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 407.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 436–437.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 461–462.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 512.

- ^ "Άμπερντην (Aberdeen), Τζωρτζ Χάμιλτον Γκόρντον, λόρδος (1784 - 1860) - Εκδοτική Αθηνών Α.Ε." www.greekencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 513–514.

- ^ "GREECE LIBERATED RECOGNITION AND ESTABLISHMENT OF DIPLOMATIC AND CONSULAR RELATIONS". International Treaties and Protocols - GREECE LIBERATED. 2021–2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 535–536.

- ^ Anderson, Rufus (1830). Observations Upon the Peloponnesus and Greek Islands, Made in 1829. Greece: Crocker and Brewster. pp. 34–35.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 519.

- ^ "TREATY OF ADRIANOPLE, BEING A TREATY OF PEACE BETWEEN THE EMPEROR OF RUSSIA AND THE EMPEROR OF THE OTTOMANS". TREATY OF ADRIANOPLE, BEING A TREATY OF PEACE BETWEEN THE EMPEROR OF RUSSIA AND THE EMPEROR OF THE OTTOMANS. 14 September 1829. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ The Revolution of 21 Dimitris Fotiadis N. Votsi Athens pp. 155-156

- ^ Loukos 1988, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Sadraddinova, Gulnara (13 October 2020). "Establishment of the Greek state (1830)". Науково-теоретичний альманах Грані. 23 (11): 91–96. doi:10.15421/1720105. S2CID 234530694.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 141.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 165.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 536.

- ^ Dimitris Fotiadis, The Revolution of 21, N. Votsi Publications Athens 1977, p. 182

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 536–537.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 187.

- ^ Dimitris Fotiadis, The Revolution of 21, N. Votsi Publications Athens 1977, p. 184

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Hatzis, Aristides (2019). "A Political History of Modern Greece, 1821-2018". Encyclopaedia of Law and Economics – via Academia.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, p. 542.

- ^ Loukos 1988, p. 173.

- ^ Beales, A. C. F. (1931). "The Irish King of Greece". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 51: 101–105. doi:10.2307/627423. JSTOR 627423. S2CID 163571443 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Loukos 1988, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Loukos 1988, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 561–562.

- ^ "The Assassination of Ioannis Kapodistrias". Greece Is. 27 September 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Παραίτηση του πρίγκηπα Λεοπόλδου". greece2021.gr. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, pp. 576–577.

Bibliography

[edit]- Issues of modern and contemporary history from the sources - OEDB 1991, Chapter 6

- Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K., eds. (1975). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΒ΄: Η Ελληνική Επανάσταση (1821 - 1832) [History of the Greek Nation, Volume XII: The Greek Revolution (1821 - 1832)] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. ISBN 978-960-213-108-4.

- Dionysios Kokkinos, The Greek Revolution, volumes I-VI, 5th edition, Melissa, Athens 1967-1969

- D.S. Konstantopoulos, Diplomatic History, vol. I, Thessaloniki 1975

- Loukos, Christos (1988). The Opposition against the Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias. Athens: 1821-1831 Historical Library-Foundation.

- Dimitris Fotiadis , The Revolution of '21, volume IV, 2nd Edition, Publisher Nikos Votsis

External links

[edit]- 1830 in London

- 1830 treaties

- Diplomacy during the Greek War of Independence

- Greece–United Kingdom relations

- Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922)

- Treaties of the Bourbon Restoration

- Treaties of the Russian Empire

- February 1830

- Ioannis Kapodistrias

- Leopold I of Belgium

- George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen