Huang Tingjian

Huang Tingjian | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

黃庭堅 | |||||||||

Huang Tingjian. | |||||||||

| Born | August 9, 1045 Xiushui County, Jiangxi, China | ||||||||

| Died | May 24, 1105 (aged 59) Cangnan County, Guangxi, China | ||||||||

| Occupation(s) | Calligrapher, painter, poet | ||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃庭堅 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄庭坚 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Luzhi | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 魯直 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 鲁直 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Shangu Daoren | |||||||||

| Chinese | 山谷道人 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Peiweng | |||||||||

| Chinese | 涪翁 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Huang Tingjian (simplified Chinese: 黄庭坚; traditional Chinese: 黃庭堅; Wade–Giles: Huang T'ing-chien; 1045, Jiangxi province, China–1105, Yizhou [now Yishan], Guangxi)[1] was a Chinese calligrapher, painter, and poet of the Song dynasty. He is predominantly known as a calligrapher, and is also admired for his painting and poetry. He was one of the Four Masters of the Song Dynasty (Chinese: 宋四家), and was a younger friend of Su Shi and influenced by his and his friends' practice of literati painting (simplified Chinese: 文人画; traditional Chinese: 文人畫), calligraphy, and poetry; regarded as the founder of the Jiangxi school of poetry.[1]

Biography

[edit]Early years in Jiangnan

[edit]

Huang Tingjian was born into the prominent Huang clan and to a family of poets,[1] which had established residence in Jiangnan, south of the Yangzi River, just across the river gorge from the main turmoils and troubles of the Five Dynasties period. Tingjian's great-great-grandfather had then and there established a great library, together with an educational system. Achievement of the jinshi degree was a common attainment for men of the Huang clan. Huang Tingjian's mother, Lady Li, was an accomplished painter of bamboo and player of the guqin. His father, Huang Shu (黃庶,1018-1058) received his jinshi in 1042, and introduced his son Huang Tingjian to the works of Du Fu and Han Yu, before dying when Tingjian was 13 years old, at which point Huang [2] Tingjian left his hometown of Fenning (分寧,in modern Jiangxi).[3]

With Uncle Li in Anhui

[edit]After his father's death, Huang Tingjian was sent to Anhui to be further brought up by his uncle, Li Chang (李常,1027-1090), who was also possessed of a large library.

Jinshi and early career

[edit]Huang Tingjian failed his jinshi in the Imperial examination, at his first attempt, in 1064, but was passed in 1067,[1] when he was 22 years old. His first employment was in Song Shenzong's first year as emperor.[4]

Tianjin earthquakes

[edit]

In 1068-1069 a series of major earthquakes occurred southwest of modern Tianjin. The devastating human consequences were noted by Huang Tingjian. This was the occasion of his writing the poem "Lament for the Refugees" (流民嘆/流民歎, using the imagery of a giant tortoise moving mountains which it carried upon its back .[5]

Teaching career

[edit]Huang Tingjian passed his teaching credential exam in 1072, and spent the next 7 years teaching at the Damingfu Imperial Academy in Hebei.[6] Its location was in what is currently Daming County. Damingfu was then Northern Capital of the Song Chinese Empire, and not far from the militarily turbulent northern border with the rival Khitan Empire.

Fame and conviction for conspiracy against the emperor

[edit]In 1072, Li Chang, his maternal uncle, and Sun Jue his father-in-law had shown examples of Huang Tingjian's works to the famous poet and New Policy opponent Su Shi (Dongpo). In 1078, Huang presented Su with a letter and two elaborate gushi-style poems, to which Su returned with two poems of his own, matching Huang's rhyme-scheme. Huang's fame was secured when Su Shi (Dongpo) heaped his praises upon him, and the two became close friends for life.[7]

So far, it seems that Huang had managed to avoid entanglement in politics, and in fact his early career as an imperial teaching official seems to have been in part secured by the favor of Wang Anshi, upon reading a poem of Huang's, hinting at retiring from the boredom which he was experiencing at that point of his career.[8] At the time, there were two major parties, a "reform" party (also known as the New Policies Group), led by Wang Anshi and a "conservative" party, which included such prominent officials as Sima Guang, Ouyang Xiu, and Su Shi. Under the imperial system the winning side was chosen by the emperor (or the emperor's regent in the case of his minority). Imperial disfavor could range from death to a stalled career.

As Emperor Shenzong increasingly favored Wang Anshi's New Policies, as they were known, their opponents suffered politically: this included exile for Su Shi, beginning in 1080, to Hangzhou (which was the time period when Su adopted the nickname of Dongpo). As Su's conviction was for writing in a defamatory way about the emperor and his government, anyone who had circulated his writings without reporting them (as Shen Kuo did), was likely to be found guilty of conspiracy. Both Huang Tingjian and his Uncle Li were convicted as co-conspirators and accordingly given considerable fines (20 catties of copper).[9] Huang was also exiled, first to Jizhou Subprefecture (now Jizhou District, Jiangxi), then to Depingzhen, in Shandong. Like, Su Shi, Huang Tingjian was known for good governance: light with taxes and empathetic with the common folk over whom they were placed in charge. Among other deeds, Huang Tingjian failed to enforce the New Policy of government monopoly of salt production.[10]

Yuanyou era

[edit]The Yuanyou (元祐, Yuányòu) era (1086–1093) was the first regnal period of the new emperor, Song Zhezong, and an important period in the life of Huang Tingjian. During the Yuanyou years, Zhezong was in his minority, and Empress Dowager Gao acted as regent. Empress Dowager Gao was not a New Policy enthusiast. Wang Anshi's party fell out of favor, and Wang Anshi himself was forced into retirement. Huang Tingjian and the other exiles were recalled from their places of banishment. Happy days were here again: now, Su, Huang, and the others could enjoy each other's company in person, and Huang was promoted, to sub-editor of the Academy of Scholarly Worthies and examining editor for the official records of former Emperor Shenzong's reign.[11] Editing the official records of the previous emperor, in light of the factional politics which had ignited at that time and were still burning, would turn out to be a perilous undertaking for Huang Tingjian's future.

Death of his mother and exile

[edit]

Huang Tingjian's mother died in 1091. Obligatory retirement for a period of mourning in the case of the death of either parent was then the custom, and Huang returned to the family cemetery in Fenning, Jiangnan, with the remains of his mother, his two wives that had died, and those of an aunt. While he was engaged in the three-year ritual mourning period, Empress Dowager Gao died, and Zhezong began to reign in fact as well as name. Zhezong favored the reformist party, and their remnant members returned with a vengeance: their opponents alive or dead were persecuted: Su Shi was demoted and exiled, Sima Guang and Lü Gongzhu's tombs were defaced, and Huang Tingjian was denounced by Cai Bian (Wang Anshi's son-in-law). Huang was convicted of sarcastically editing the official records of former Emperor Shenzong. Huang Tingjian spent the ensuing decade in exile, in various locations in Sichuan.[12]

Pardon and exile, again

[edit]

In the year 1100, Emperor Zhezong died young and unexpectedly, at 23 years old, and with his death came a new political alignment: the new emperor was Huizong, then in his late teenage years. Much of the power was in the hands of his older brother's wife, the former Empress Xiang. A general amnesty was declared between the two parties, the reformists and, the conservatives. By this time the anti-reformist conservatives were known as the "Yuanyou Party". Cai Bian and his adherents were dismissed from office. Huang Tingjian found out he had been pardoned, later in the year of 1100. He was also granted a sinecure position in Ezhou city, in southeastern Hubei (responsible for collecting tax revenues on salt), which meant that he received a salary or other remuneration; but, as he was not required to live or work there, this was not exile. However, Huang Tingjian remained in Sichuan long enough to attend his son's marriage ceremony, to the daughter of a local official. In 1102, Huang Tingjian visited Fenning, after extensive travels and several illnesses. As the year 1102 progressed, the political pendulum again reversed itself: the Yuanyou officials were out of favor once more. A list of somewhat over 100 officials whom the emperor considered to be heterodox was erected on a stele at the capital: Huang Tingjian was one of those named. Huang had been the recipient of a major promotion, but was now dismissed summarily, just 9 days after his appointment. As the year 1102 waned, Huang Tingjian returned to Ezhou, and visited various other places including Wuchang. It was during this period that he wrote "Wind in the Pines Hall".[13] Huang Tingjian awaited further developments at Ezhou, hearing no news about how the emperor intended to deal with his case, until the end of 1103. It was exile, again. This time to the far south, Yizhou (now in Guangxi).[14] At the time, as now Yizhou, was a fairly small settlement composed of both ethnic Han people and Zhuang people. However, then it was only tenuously part of the Chinese Empire. Guangxi, then administered as Guangnanxi ("West Southern Expanse"), had only been annexed by the Song Dynasty in 971. And, as recently as 1052, the Zhuang leader Nong Zhigao had led a revolt, briefly making the area part of an independent kingdom. Sending the then 58-year-old, sick and frail Huang Tingjian to an official exile in this remote and precarious position was not far from a death sentence.

XiaoXiang poetry

[edit]

Travel to his remote posting meant passing through the XiaoXiang: the classic poetic place of exile. Not that he was not already there, in Ezhou; but, now, Huang Tingjian was faced with traveling through the depths of it, only to emerge into an even more remote and difficult territory. He faced a fate similar to Su Shi Dongpo, who never quite made it back from his final exile in the then remote and undeveloped island of Hainan. The far southern lands were known as the "gates of hell", but when the emperor ordered one of his subjects there, there was little choice. Open resistance could be and often was met with the mass annihilation of ones entire family, and even whole clan. The main hope was a quick recall from exile. However, in Huang Tingjian's case, this never happened.

In early 1104, Huang Tingjian packed up his family and headed south, towards his place of banishment, Yizhou. That springtime, during the course of his journey, Huang Tingjian met the Chan monk Zhongren (also known as Huaguang, after the name of his monastery). Zhongren shared a scroll of poems by Su Shi, Su Shi's brother Su Che, the monk Shenliao, and Qin Guan (another one of the Yuanyou crew): and, both Su Shi and Qin Guan had died as a result of their exiles in the south, the journey which Huang Tingjian was now upon.

The two became friends: Zhongren painted branches of flowering plum blossoms and landscapes for Huang, Huang wrote poems in his inimitable calligraphy for Zhongren, even appending a poem with praise of Zhongren to the end of his precious scroll of poems. Together the two helped to change the art world forever: establishing monochrome painting of plums among the scholar-official class.[15]

Death

[edit]

Parting ways with his friend Zhongren, Huang Tingjian headed onward towards his destined place of banishment, Yizhou. Emperor Huizong had ordered him there, and so, leaving his family in the mountains of Yongzhou (Hunan), in order to "spare them from the intense heat", Huang Tingjian traveled on to his destination without them.

Once there, he continued his calligraphy, of which an ink rubbing survives, a rather pointed quote about the life of Fan Pang (137-169), who was arrested and executed due to getting caught up in factional politics, during the second of the Disasters of Partisan Prohibitions which occurred during the Han dynastic era.[16]

In the early Winter of 1105, Huang Tingjian died, alone from his family, in exile, in Yizhou.

His funeral was arranged by a stranger, who had traveled to Yizhou, hoping to make his acquaintance.[17]

Health

[edit]Huang Tingjian's health was poor throughout his life. His health problems included "beriberi, severe coughs and colds, malarial fever, headaches, dizziness, and in his later years, heart trouble and chest and arm pains."[18] Huang Tingjian also had a deep interest in medicinal substances, and at one point seriously mulled over the idea of giving up his aspirations for an official career, in favor of opening up a shop and dealing in herbs and herbal medications.[19]

Family

[edit]Huang Tingjian had 3 wives during his life, and one son, to the third. His first wife was the daughter of the scholar, Sun Jue (1028-1090). She died in 1070. His second wife, from the Xie clan, had a daughter to him, before her death, in Damingfu, in 1079. His third wife gave birth to his only son, whom he gave the unusual name of "Forty", because he was 40 years old when the boy was born.[20]

Religion

[edit]Huang Tingjian had a strong lifelong interest in Buddhism and Daoism. In his hometown of Fenning were 10 monasteries of the Chan practice ("Chan" is Chinese for Zen); indeed, Jiangnan had hundreds of them. The year after his second wife died, Huang retreated to the Shan'gu (Mountain Valley) Daoist monastery in Anhui, and took the religious name Shan'gu Daoren.[21]

Works

[edit]

Huang Tingjian is noted for his prodigious talent in terms of his vast knowledge of Classical Chinese poetry and literature.[23] He is famous both for the calligraphy and the poetry of his work "Wind in the Pines Hall", which survives in the Palace Museum, Taipei.[24]

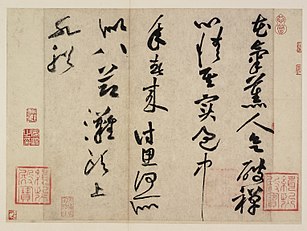

Calligraphy

[edit]

Huang is also regarded as a particularly fine and creative calligrapher of the Song Dynasty. His xingshu (semi-cursive style of script) displays a sharpness and aggression that is instantly recognizable to students of Chinese calligraphy. His calligraphic piece Biographies of Lian Po and Lin Xiangru epitomises a technique today known as "flying-white" "when writing calligraphy, the areas within a brushstroke where the brush fails to leave a full measure of ink and streaks of white paper or silk appear".[25]

Poetry

[edit]Huang Tingjian is considered to be the founder of the Jiangxi school of poetry.[26]

Gallery

[edit]-

Picture of Huang Tingjian, from much later times.

-

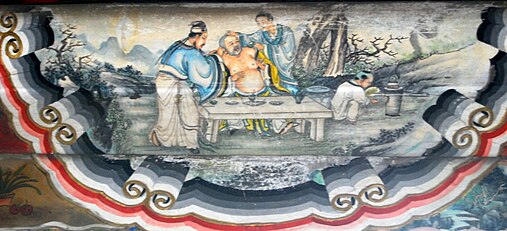

Illustration from the Long Corridor. Left to right: Su Shi, Fo Yin (佛印), and Huang Tingjian, drinking wine.

-

Wei Qing Dao Ren Observance

-

Besotted by Flower Vapors

-

24 paragons of filial piety - Huang Tingjian, who "so loved his mother, that he emptied her chamber pot himself".

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Huang Tingjian | Song Dynasty, Calligraphy, Poetry | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-11-23.

- ^ Murck, 158-159

- ^ Murck, 158 and 161

- ^ Murck, 158

- ^ Murck, 160 and note 3, page 331

- ^ Murck, 158-159

- ^ Murck, 159 and note 8, page 331

- ^ Murck, 158-159

- ^ Murck, 160-161

- ^ Murck, 158-160

- ^ Murck, 160

- ^ Murck, 161-162

- ^ Murck, 162-163

- ^ Murck, 179

- ^ Murck, 179

- ^ Murck, 187. Also see 後漢書/卷67

- ^ Murck, 187-188

- ^ Murck, note 5, page 331, following Shen Fu

- ^ Murck, 159

- ^ Murck, 159

- ^ Murck, 159

- ^ Patton, Andy J. (2013). ""A Painter's Brush That Also Makes Poems": Contemporary Painting After Northern Song Calligraphy". Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository, Paper 1302.

- ^ Murck, 157

- ^ Murck, 177

- ^ Wang Yao-t'ing, Looking at Chinese Painting, Nigensha Publishing Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan (first English edition 1996), p, 78. ISBN 4-544-02066-2

- ^ Murck, 157

References

[edit]- Encyclopædia Britannica, copyrighted 1994-2005.

- Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute. ISBN 0-674-00782-4.

- Willets, William, Chinese Calligraphy: Its History and Aesthetic Motivation, Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Wang Yao-t'ing, Looking at Chinese Painting, Nigensha Publishing Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan (first English edition 1996), p, 78. ISBN 4-544-02066-2

External links

[edit]- Huang Tingjian's Calligraphy Gallery at China Online Museum

- 1045 births

- 1105 deaths

- 11th-century Chinese calligraphers

- 11th-century Chinese painters

- 11th-century Chinese poets

- 12th-century Chinese calligraphers

- 12th-century Chinese painters

- 12th-century Chinese poets

- Painters from Jiangxi

- People from Jiujiang

- Poets from Jiangxi

- Song dynasty calligraphers

- Song dynasty painters

- Song dynasty poets

- Song dynasty Taoists

- 12th-century Taoists

- 11th-century Taoists

- Twenty-four Filial Exemplars