Banovci, Vukovar-Syrmia County

Banovci

Šidski Banovci | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s): | |

| |

| Coordinates: 45°11′06″N 19°03′55″E / 45.184934°N 19.065382°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Syrmia (Podunavlje) |

| County | |

| Municipality | Nijemci |

| Established | 1730s (as the new village of Banovci) |

| Government | |

| • Body | Local Committee |

| Area | |

• Total | 10.5 km2 (4.1 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[4] | |

• Total | 256 |

| • Density | 24/km2 (63/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Banovčanin (♂) Banovčanka (♀) (per grammatical gender) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 32247 Banovci |

| Vehicle registration | VK |

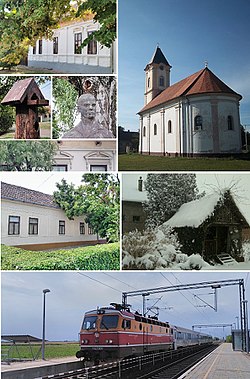

Banovci (German: Schider Banovci,[5] Serbian Cyrillic: Бановци / Шидски Бановци,[6] Hungarian: Forró / Újbánóc);, also known as Šidski Banovci, is a village located in the Vukovar-Syrmia County of Croatia, near the Serbian border.[2] The village had a population of 256 as of the 2021 census.

Originally settled in the 1730s as the new village of Vinkovački Banovci, it is today part of the Nijemci Municipality. The village of Banovci has undergone several name changes over the past, reflecting the shifting political landscapes of the region. Historically referred to as "Small Switzerland," Banovci has a rich cultural and historical legacy, influenced by its Danube Swabians Protestant settlers. Today, the village is primarily inhabited by a Serb community and is known for the local Serbian Orthodox Church of the Holy Venerable Mother Parascheva, and its local football club, NK Borac, established in 1940.

The village is connected with the rest of the country by the D46 state road connecting it with the town of Vinkovci and continuing into Serbia as the State Road 120 to the nearest town of Šid and by the Zagreb–Belgrade railway and the Šidski Banovci railway station.

Name

[edit]

The village of Banovci has undergone several name alterations over the years. Prior to 1900, it was known as "Novi Banovci" (New Banovci), and from 1910 to 1991, it was called "Šidski Banovci".[7] In 1991, at the early stages of the Croatian War of Independence, the first word was formally removed from the name, but due to village's association with the self-proclaimed SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia, the old name continued to be officially used in administration until 1998, marking the end of the UNTAES transitional administration over the region. Many local residents still use the old name to this day.

A notable error occurred in the National Law on 1997 Croatian local elections when the name "Šidski Banovci" was mistakenly retained instead of using "Banovci".[8] The term "Šidski" is a possessive adjective derived from the nearby town of Šid, situated 12 kilometers away in neighboring Serbia.

Adjacent to Banovci is another village with a similar name, known as Vinkovački Banovci by the town of Vinkovci. Interestingly, the Croatian Railways, the national railway company, still refers to the local railway station as "Šidski Banovci railway station." This old name was also used in a 2005 investigative report by The New York Times.[9] Furthermore, the 2017 Report on County Roads, published by Vukovar-Syrmia County in March 2018, still included the previous name "Šidski Banovci" on the map and in the textual analysis.[10]

The name of the village, whether referred to in Croatian or Serbian, is plural in form.

History

[edit]Habsburg Monarchy

[edit]The present-day village of Banovci was established in the 1730s under the name "New Banovci," situated adjacent to the older village known as modern-day Vinkovački Banovci, which was already mentioned in historical records as far back as the 15th century.[2] In 1473, the village was referred to as "Zavrakinci," and it was located on a small uplift of the Vukovar Plateau just northwest of the current village, where local vineyards are found up until today.[2] The initial influx of Serb settlers to Banovci occurred during the reign of Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor in what is known as the Great Migrations of the Serbs.[2] These settlers originated from what is now known as Montenegro and the region around Peć in Kosovo.[2]

The year 1745 saw the establishment of the Slavonian Military Frontier in the region, marking an important historical development in the area's governance and defense in the Habsburg monarchy.[2]

Austria-Hungary

[edit]

In 1859, the first Danube Swabians settled in Banovci.[2] These Protestant German settlers sought the assistance of the local Serbian Orthodox priest named Uroš during their initial years in the new region.[2] Priest Uroš believed that the arrival of the German settlers could help bring about reforms, particularly in agricultural practices.[2] However, due to predetermined areas for German Catholic colonists in the northern part of the historical region of Syrmia, and the difficulty of settlement in most of the Slavonian Military Frontier, the German Protestants had to establish themselves in the bordering region between these two jurisdictions, with Banovci being one of the few places where this was possible.[2]

At the time of the German settlers' arrival, the local Serbian population exercised its local autonomy through the election of a mayor who held the honorary title of the village prince.[2] Nevertheless, the true spiritual and secular power was in the hands of the Orthodox priest.[2] An interesting incident occurred when the first German colonist family, the Grumbachs, offered sausages made from a German recipe to their neighbors. The local young men, impressed by the quality of the sausages, started coming to the Grumbachs' household, demanding to be given the sausages.[2] However, this led to some disruptive behavior. Upon learning of the situation, the German colonists sought the assistance of priest Uroš, who confronted the young men and prohibited them from repeating such actions.[2] As compensation, he asked each of the young men to provide one pig to the Grumbachs' household.[2]

As the Evangelical Reformed Church in Šidski Banovci was not built at the time, the German Protestant settlers approached priest Uroš with a request to hold a Christmas liturgy for them under the Eastern Orthodox liturgical rite.[2] However, he declined the request, citing its contradiction with Orthodox canonical rules.[2] Instead, he suggested that they organize their own Christmas celebration at the Church of the Holy Venerable Mother Parascheva in the village, which he attended, though he did not lead the prayer.[2]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

[edit]During the period of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Banovci were included in the administrative region of Šid Srez. Initially, they were part of the Syrmia County before Yugoslavia was officially established and up to 1922. Subsequently, they became part of the Syrmia Oblast from 1922 to 1929. Afterward, during the years 1929 to 1939, they were incorporated into the Danube Banovina. Finally, from 1939 to 1941, Banovci fell under the jurisdiction of the Banovina of Croatia.

World War II

[edit]During World War II in Yugoslavia, Banovci became a settlement for survivors of the Ivanci massacre.[11] On 15 June 1943, the German Volke Group in the Independent State of Croatia reported a decline in morale due to the activities of the Yugoslav Partisans.[12] As a result, Friedrich Hoffman assumed leadership of their local group in Šidski Banovci, taking over from Karl Lahm.[12] In July 1943, Nazi forces destroyed agricultural machinery, including threshers, across several villages, including Banovci.[13]

Banovci itself became a significant center for the Yugoslav Partisans in Syrmia, focusing primarily on sabotaging Nazi and quisling transportation along the Zagreb–Belgrade railway. Notably, on 8 October 1943, the Sabotage Group of the Second Syrmia NOP detachment mined the Zagreb–Belgrade railway, resulting in the destruction of a locomotive and six freight wagons.[14] In retaliation, the Ustasha police hanged 20 hostages from Šid the following day as an act of revenge for the sabotage.[14] Subsequent sabotage of the railway occurred on 19 October 1943, when a locomotive and four wagons of a German express train were destroyed.[15] A third successful sabotage took place on 2 December 1943, targeting a German military freight train carrying war material, which was mined and destroyed along with the locomotive and eight wagons.[16]

Slobodan Bajić Paja, who became a People's Hero of Yugoslavia for his bravery and heroism during the war, hailed from Šidski Banovci.

Post-War establishment of the border between Yugoslav Republics of Serbia and Croatia

[edit]Some minor border demarcation issues between the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, a part of the Socialist Republic of Serbia, and Socialist Republic of Croatia (both part of the FPR Yugoslavia) were left unresolved by the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia by the 24 February 1945 and the end of the war. In order to settle the matter, in June 1945 the federal authorities set up a five-member commission presided over by Milovan Đilas.[17]

District of Šid was identified as one of the points of territorial dispute. Commission concluded that District of Šid, including the village of Banovci at the time, shall become a part of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina.[17] Commission's demarcation was nevertheless subsequently altered changed in several instances including in the case of District of Šid where villages Tovarnik, Ilača and Banovci were ultimately transferred to the Socialist Republic of Croatia.[17] Both Ilača and Tovarnik were larger, ethnically Croat villages, while Banovci as a smaller Serb village which until recently had German majority was transferred to Croatia in order to ensure territorial contiguity.

Yugoslav Communist authorities claimed that local self-determination referendums took place on which population decided to become join Croatian federal unit.[17] In 2015 article in right wing conservative Nova srpska politička misao quarterly magazine, Igor Marković claimed that there is no any evidence that any such local referendum ever took place in Banovci and other villages and argued that based on that Serbia shall request return of those settlements or on reciprocal right of self-determination for Serb settlements in Eastern Slavonia.[17] Territory of the District of Šid was changed a couple of times in the mid 1940s including changes within the Province of Vojvodina with most of them having minimal daily consequences during the existence of Yugoslav state.

Socialist Republic of Croatia

[edit]Croatian War of Independence and United Nations Mission

[edit]On 7 January 1991 Serb National Council of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia was established in Banovci subsequently leading to the establishment of the self-proclaimed SAO Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia in the same year.[18] During the War Banovci were part of the self-proclaimed entity. Between 1995 and 1998 Banovci were part of the temporary United Nations governed protectorate aimed at its peaceful reintegration under the rule of the Republic of Croatia. Within the unrecognized Republic of Serbian Krajina Banovci was a de facto part of parallel Mirkovci Municipality which was established on the part of pre-War Yugoslav Vinkovci Municipality under the rebel control.

Post-1998 History

[edit]In 1998 in addition to de jure Banovci became de facto part of Nijemci Municipality and Vukovar-Syrmia County. Banovci is a settlement within the Areas of Special State Concern belonging to the first among the three groups. In 1998 in addition to de jure Banovci became de facto part of Nijemci Municipality and Vukovar-Syrmia County. Banovci is a settlement within the Areas of Special State Concern belonging to the first among the three groups. In 2005 village was shortly in the spotlight of international media when The New York Times discovered it to be a location of hiding of Slobodan Davidović, a former member of Scorpions paramilitary accused and subsequently convicted on 15 years in prison for war crimes related to Srebrenica genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[9] While Serbian police described him as being in hiding The New York Times discovered that he "has been here on and off since the end of war, staying with his elderly mother and brother in a small house off the village high street".[9] In 2012 non-governmental organization "Ivanci" was established in the village aimed at reconstruction of the monument in the memorial area, collection of materials for the publication of a monograph and organization of commemorations for victims of Ivanci massacre.[19] In early 2019 villages of Tovarnik, Ilača and Banovci organized joint demonstrations against truck drivers from countries other than Croatia and Serbia which are causing heavy traffic congestion on the D46 road while waiting to cross the state border between Croatia and Serbia.[20][21] Citizens requested redirection of all truck transportation, with the exception of Croatian and Serbian trucks traveling to one or the other state, to be removed from the D46 road and redirected to A3 motorway.[20] Later in 2019 village celebrated 200 years of the local orthodox church and 800 years of autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church.[22]

Languages

[edit]Due to the fact that Serbs of Croatia constitute majority population in the village, the Nijemci Municipality allows the equal official use not only of Croatian language, but the Serbian language and Serbian Cyrillic alphabet as well.[23][6]

Demographic

[edit]The village is home to over 400 inhabitants most of whom have declare themselves Orthodox Christians and Serbs.

Major source of income is agriculture or work in nearby towns of Vukovar, Vinkovci and Šid. Population is faced with high unemployment rates, aging population and emigration of young and educated individuals.

| Population[24] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1857 | 1869 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1921 | 1931 | 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

| 460 | 779 | 651 | 836 | 890 | 990 | 1047 | 1139 | 1028 | 1138 | 1084 | 975 | 778 | 653 | 479 | 438 |

History of Germans in Banovci

[edit]Before World War II, Banovci was primarily inhabited by the Protestant Danube Swabians, who had initially settled in the existing Serbian village in the 1740s.[2] According to the 1910 census, Banovci had a total of 990 residents, with 668 of them being Germans. Over time, the German community had developed a strong social life and established various public institutions, with the local Evangelical Reformed Church in Šidski Banovci being the central one among them.[2] Adjacent to the church was the school, which also served as the town hall, and a local savings bank was conveniently nearby. The village's residents valued and upheld traditional values, and they were known for their strong work ethic.

However, towards the end of 1944, the German villagers of Banovci found themselves in a precarious situation and had to hastily evacuate the area due to the widespread retaliations for Nazi crimes. The new post-war government declared ethnic Germans in Yugoslavia as non-citizens and seized their property.[2] By 1945, nearly 500,000 Germans were expelled, a process referred to as "transfer" in Article XIII of the Potsdam Agreement, from Yugoslavian territory. In the case of Banovci, the residents received some warning from the Nazi German Army about the impending necessity to leave their homes and evacuate the village. Consequently, on October 17, a caravan of 40 to 50 families, with the church bells ringing in the background, departed from the village, heading northwest over Hungary, towards Austria and Germany.

Religion

[edit]Serbian Orthodoxy

[edit]

The neoclassical St. Petka's Church was completed in 1819. The church and its parish are under jurisdiction of Eparchy of Srem which is based in Sremski Karlovci in neighbouring Serbia. The church is dedicated to Saint Parascheva of the Balkans.

Pentecostalism

[edit]First Pentecostal activities in Banovci started in 1920.[25] For beginning of activities of this religious group is connected story about miracle cures of local girl Elizabeth Spies.[25]

Calvinism

[edit]Evangelical Lutheranism

[edit]Culture

[edit]Every year on the Orthodox Christmas Eve (January 6), residents in the churchyard have a bonfire for "Badnjak", the Serbian word for Christmas Eve. In this occasion locals take oak trees from the area and make a ritual fire. These nights the locals remember their old Slavic religion and symbolically confirm Christianity.

In the rest of the year, villagers are organized around the celebration of New Year's, Women's Day, labor day, the occasion of the end of the school year, important religious holidays, etc. The football club, pensioners club, the Protestant community and the Women's Caucus, which also periodically organizes public events, are active participants.[note 1]

Education

[edit]

The Elementary School Ilača-Banovci is a primary educational institution in the area of Ilača, Banovci, and Vinkovački Banovci. The school offers classes taught in both Croatian and Serbian languages. Formerly, the Banovci School served as the center of school administration until it was relocated to Ilača in 2002.[26] In Banovci, classes are conducted in the Serbian version of the Serbo-Croatian language. The school is centrally located within the Banovci and includes amenities such as a small gym, garden, and football field. Besides the standard Croatian school curriculum conducted in Serbian, students in Banovci are also required to take additional subjects, such as Serbian Language, History of Serbia, Geography of Serbia, and Arts and Music of Serbia and elective Orthodox Religion Education. Throughout the academic year, the school organizes several annual celebrations that engage the entire local community. These events include the commencement of the school year, Bread Day, Sports Day, St. Sava Day, and the end-of-year celebration.

Sport

[edit]NK Borac is a football club located in Banovci. Established in 1940 by a group of enthusiastic local football fans, the club's name "Borac" translates to "Fighter," paying homage to the local Partisan soldiers who fought during World War II. The club possesses and operates the local playground in Banovci. Over the years, NK Borac has consistently achieved commendable results in the 3 County League, consistently ranking among the top three clubs. Financial support for NK Borac primarily comes from donations contributed by the local community, the municipality, and various local businesses. Apart from their regular football activities, NK Borac Banovci has undertaken an initiative called the "Sport Day" in collaboration with local schools. Held annually in the spring, this event sees students being excused from their regular classes to participate in various sports competitions at the Borac field. These competitions encompass a wide range of sports, including football, racing, and traditional sports.

See also

[edit]Notable natives and residents

[edit]- Slobodan Bajić Paja

- Günter Stock (President of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities 2006-2015, Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities 2008-2015 and the All European Academies since 2012)[27]

- Milorad Kosanović

Notes

[edit]- ^ Banovci are one of the last places in Croatia that has retained its street names from the period of communist Yugoslavia. This was done at the express request of the villagers. For this reason, the name of the main street still bears the name of former Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito, while other streets are named by prominent members of the anti-fascist movement during World War II.

References

[edit]- ^ Government of Croatia (October 2013). "Peto izvješće Republike Hrvatske o primjeni Europske povelje o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima" (PDF) (in Croatian). Council of Europe. p. 34. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Život i rad švapske obitelji Kettenbach u Novim-Šidskim Banovcima od doseljenja do Velikoga rata" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-21. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Register of spatial units of the State Geodetic Administration of the Republic of Croatia. Wikidata Q119585703.

- ^ "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements" (xlsx). Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in 2021. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2022.

- ^ "Syrmia Village Index". Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Registar Geografskih Imena Nacionalnih Manjina Republike Hrvatske" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ^ https://web.dzs.hr/hrv/pxweb2003/Dialog/Footnote.asp?File=Tabela4_16.px&path=../Database/Naselja%20i%20stanovnistvo%20Republike%20Hrvatske/4%20Stanovnistvo%20naselja/&ti=Vukovarsko-srijemska+%9Eupanija+-+broj+stanovnika+po+naseljima+&lang=10&ansi=1[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Ispravak Zakona o izbornim jedinicama za izbor članova predstavničkih tijela jedinica lokalne samouprave i jedinica lokalne uprave i samouprave" (in Croatian). Narodne novine. 21 February 1997. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Wood, Wood (13 June 2005). "On TV, Serb's Violent PastCatches Up With Him". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Izvješće o poslovanju Uprave za ceste VSŽ za 2017. godinu" (PDF) (in Croatian). Vukovar-Srijem County. 21 February 1997. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Šašić, Tijana (25 March 2017). "Ivanci – selo kojeg više nema". Privrednik. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ a b Nada Lazić, ed. (1986). Građa za historiju Narodnooslobodilačkog pokreta u Slavoniji, Knjiga VI (1. VI — 31. VII 1943) [Sources for the History of the People Liberation Movement in Slavonia, Book VI (1. VI — 31. VII 1943)] (in Serbo-Croatian). Slavonski Brod: Historijski institut Slavonije. p. 192.

- ^ Veljko Maksić; Nebojša Vidović (2022). Сведоци времена: историјски преглед развоја села Остеова [Witnesees of Time: Historical Review of the Development of the Ostrovo Village]. Vukovar: Joint Council of Municipalities. ISBN 978-953-8489-02-0.

- ^ a b "Kod s. Šidskih Banovaca Diverzantska grupa 2. sremskog NOP odreda minirala prugu Šid-Vinkovci i uništila lokomotivu i 6 vagona teretnog voza". Arhiv Znaci. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Između s. Ilače i s. Šidskih Banovaca (kod Šida) Diverzantska grupa 2. sremskog NOP odreda minirala prugu i uništila lokomotivu i 4 vagona nemačkog brzog voza". Arhiv Znaci. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Između s. Ilače i s. Šidskih Banovaca (kod Šida) Diverzantski udarni bataljon GŠ NOV i PO za Vojvodinu bataljon minom izbacio iz šina nemački vojni teretni voz sa ratnim materijalom i uništio lokomotivu i 8 vagona". Arhiv Znaci. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Afera "Piranski zaliv" kao opomena za predstojeću hrvatsku ofanzivu na Dunavu". Archived from the original on 2018-08-09. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Banovci". Archived from the original on 2018-08-09. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Udruga Ivanci". Fininfo. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Kolone kamiona zagorčavaju život stanovnicima Tovarnika: Imam osjećaj da se nalazimo u '91. kad smo bili pod okupacijom". Dnevnik.hr. 18 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Ili zabrana za teške kamione ili blokada ceste". Glas Slavonije. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Večeras zajedno". Radio Television of Serbia. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Izvješće o provođenju ustavnog zakona o pravima nacionalnih manjina i o utošku sredstava osiguranih u državnom proračunu Republike Hrvatske za 2008. godinu za potrebe nacionalnih manjina, Zagreb, 2009.

- ^ - Republika Hrvatska - Državni zavod za statistiku: Naselja i stanovništvo Republike Hrvatske 1857.-2001.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Kovačević, David (June 2013). "Prikaz razvoja Crkve Božje u Banovcima". Kairos: Evanđeoski teološki časopis (in Croatian). VII (1). Osijek. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

- ^ "Odluka o promjeni sjedišta Osnovne škole Ilača-Banovci" (PDF). Službeni vjesnik. Vukovar-Srijem County. 2002-05-02. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- ^ Stock, Günter (2018). Building Bridges Connecting European Excellence Selected speeches by Günter Stock. All European Academies.