Erec and Enide

| Erec and Enide | |

|---|---|

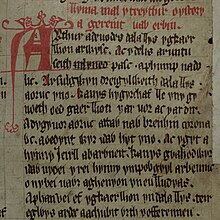

The White Stag hunt in a medieval manuscript | |

| Original title | French: Érec et Énide |

| Author(s) | Chrétien de Troyes |

| Language | Old French |

| Date | c. 1170 |

| Genre | Chivalric romance |

| Verse form | Octosyllable rhyming couplets |

| Length | 6,598 lines |

| Subject | Arthurian legend |

| Personages | Erec, Enide, Yder |

Erec and Enide (French: Érec et Énide) is the first of Chrétien de Troyes' five romance poems, completed around 1170. It is one of three completed works by the author. Erec and Enide tells the story of the marriage of the titular characters, as well as the journey they go on to restore Erec's reputation as a knight after he remains inactive for too long. Consisting of about 7000 lines of Old French, the poem is one of the earliest known Arthurian romances in any language, predated only by the Welsh prose narrative Culhwch and Olwen.[1][2]

Synopsis

[edit]Approximately the first quarter of Erec and Enide recounts the tale of Erec, son of Lac, and his marriage to Enide, an impoverished daughter of a vavasor from Lalut. An unarmored Erec is keeping Guinevere and her maiden company while other knights participate in a stag hunt near Cardigan when a strange knight, a maiden, and his dwarf approach the queen and treat her servant roughly. At the queen's orders, Erec follows the knight, Yder, to a far off town where he meets and falls in love with Enide. He borrows a set of armor from the vavasor and goes with Enide to claim a sparrow-hawk that belongs to the most beautiful maiden in the town. Erec challenges and defeats Yder for the sparrow-hawk and they return to Enide's father, who gives permission for the two to marry. Erec refuses to accept gifts of new clothes for Enide and takes her to Arthur's court in her ragged chemise. In spite of her appearance, the courtiers recognize Enide's inherent nobility and Queen Guinevere dresses her in one of her own richly embroidered gowns. Erec and Enide are married, and Erec wins a tournament before getting permission to leave with his wife.

The central half of the poem begins some time later when rumors spread that Erec has come to neglect his knightly duties due to his overwhelming love for Enide and his desire to be with her. He overhears Enide crying over this and orders her to prepare for a journey to parts unknown. He commands her to be silent unless he speaks to her first, but she disobeys him to warn him when they are pursued by two different groups of knights. Both times, Erec scolds Enide before defeating the knights. When they stay overnight in a village, a count visits and threatens to kill Erec if Enide doesn't sleep with him. She warns Erec the next morning and they escape, but the count and a hundred knights give chase, and Enide breaks her silence again to warn Erec. Erec defeats a seneschal and a count before he and Enide flee into the forest, where he defeats and befriends Guivret the Short, an Irish lord with family connections to Pembroke and Scotland. Erec and Enide continue travelling until they find King Arthur's men, but Erec refuses their hospitality and continues travelling. He rescues Cadof of Cabruel from two giants, but the fighting reopens his injuries and Erec falls down as though dead. Enide is found by Count Oringle of Limors, who takes Erec's body with him and tries to marry Enide. Enide's anguish is enough to wake up Erec, who kills the count and forgives Enide for having broken her silence throughout their journey. Guivret hears of Erec's supposed death and sends a thousand men to seize the castle to avenge his friend, but he doesn't realize he is fighting Erec until Enide steps in and stops him, telling him of Erec's identity.

The last quarter of the poem adds another episode, referred to as the "Joy of the Court," in which Erec frees King Evrain's nephew Maboagrain from an oath to his lover that had prevented him from leaving the forest until defeated in combat. This causes a great deal of celebration, and Enide learns that the maiden is her cousin. Erec and Enide then travel to Nantes, where they are crowned King and Queen in a lavishly described ceremony.[3]

Motifs/themes

[edit]Erec and Enide displays the themes of love and chivalry that Chrétien de Troyes continues in his later work. Tests play an important part in character development and marital fidelity. Erec's testing of Enide is not condemned in the fictive context of the story, especially when his behaviour is contrasted with some of the more despicable characters, such as Oringle of Limors.[4] Nevertheless, Enide's faithful disobedience of his command to silence saves his life.

Another theme of the work is Christianity, as evidenced by the plot's orientation around the Christian Calendar: the story begins on Easter day, Erec marries Enide at Pentecost, and his coronation occurs at Christmas.[5]

In the 12th century, conventional love stories tended to have an unmarried heroine, or else one married to a man other than the hero. This was a sort of unapproachable, chaste courtly love. However, in Erec and Enide, Chrétien addressed the less conventionally romantic (for the time period) concept of love within marriage. Erec and Enide marry before even a quarter of the story is over, and their marriage and its consequences are actually the catalysts for the adventures that comprise the rest of the poem.[6]

Gender also plays an important role. Enide is notable for being very beautiful, as Erec asks to bring her along so that she can retrieve the sparrow-hawk towards the start of the story. Enide is also outspoken despite Erec's instruction for her to stay silent, however, and there is debate between scholars about whether Erec and Enide is meant to be a positive portrayal of women or whether Enide's free speech should be seen as good or bad. Erec criticizes and threatens Enide for warning him of danger, but it is Enide's refusal to stay silent that not only awakens Erec, but that ends the fighting between Erec and Guivret when Erec is weakened. Erec's masculinity is also the reason that he and Enide go on a journey in the first place: his inactivity causes many to speculate that Enide has somehow weakened him, making him an object of ridicule.[7]

Importance

[edit]Chrétien de Troyes played a primary role in the formation of Arthurian romance and is influential up until the latest romances. Erec et Enide features many of the common elements of Arthurian romance, such as Arthurian characters, the knightly quest, and women or love as a catalyst to action. While it is not the first story to use conventions of the Arthurian characters and setting, Chrétien de Troyes is credited with the invention of the Arthurian romance genre by establishing expectation with his contemporary audience based on its prior knowledge of the subjects.

Enide is notable in Chrétien's work for being the only woman to be named in the title.[8]

Popular in its own day, the poem was translated into several other languages, notably German in Hartmann von Aue's Erec and Welsh in Geraint and Enid, one of the Three Welsh Romances included in the Mabinogion. Many authors explicitly acknowledge their debt to Chrétien, while others, such as the author of Hunbaut, betray their influence by suspiciously emphatic assurance that they are not plagiarizing. However, these tales are not always precisely true to Chrétien's original poem, such as in Geraint and Enid, in which Geraint (unlike Erec) suspects Enid of infidelity.[9]

Manuscripts and editions

[edit]Erec and Enide has come down to the present day in seven manuscripts and various fragments. The poem comprises 6,878 octosyllables in rhymed couplets. A prose version was made in the 15th century. The first modern edition dates from 1856 by August Immanuel Bekker, followed by an edition in 1890 by Wendelin Foerster.

Literary forebears

[edit]Wittig has compared aspects of the story to that of Dido, Queen of Carthage and Aeneas in Virgil's Aeneid. Enide does not lose her lover or commit suicide but many connections can be shown between Erec's gradual maturing process throughout the story and Aeneas's similar progress.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Koch, J. T., Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2006, p. 861.

- ^ Duggan, Joseph J., The Romances of Chrétien de Troyes, Yale University Press, 2001, p. 200

- ^ Four Arthurian Romances by Chrétien de Troyes at Project Gutenberg

- ^ Mandel.

- ^ Chrétien; Cline.

- ^ Chrétien; Cline.

- ^ Ramey, Lynn Tarte. "Representations of Women in Chrétien's Erec et Enide: Courtly Literature or Misogyny?" Romantic Review 84 no. 4 (Nov. 1993): 377-380.

- ^ Ramey, Lynn Tarte. "Representations of Women in Chrétien's Erec et Enide: Courtly Literature or Misogyny?" Romantic Review 84 no. 4 (Nov. 1993): 377-386.

- ^ De Troyes, Chretien. "Introduction." Introduction. Erec and Enide. Trans. Ruth Harwood. Cline. Athens: University of Georgia, 2000. xx. Print.

- ^ Wittig.

Sources

[edit]- Adler, Alfred (1945). "Sovereignty as the Principle of Unity in Chrétien's "Erec'". PMLA Volume 60 (4), pp. 917–936.

- Busby, Keith (1987). "The Characters and the Setting". In Norris J. Lacy, Douglas Kelly, Keith Busby, The Legacy of Chrétien De Troyes vol. I, pp. 57–89. Amsterdam: Faux Titre.

- Chrétien de Troyes; Cline, Ruth Harwood (translator) (2000) "Introduction." Introduction. Erec and Enide. Athens: University of Georgia, 2000. Print.

- Chrétien de Troyes; Owen, D. D. R. (translator) (1988). Arthurian Romances. New York: Everyman's Library. ISBN 0-460-87389-X.

- Lacy, Norris J. (1991). "Chrétien de Troyes". In Norris J. Lacy, The New Arthurian Encyclopedia, pp. 88–91. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-4377-4.

- Lacy, Norris (1987). "Preface". In Norris J. Lacy, Douglas Kelly, Keith Busby, The Legacy of Chrétien De Troyes vol. I, pp. 1–3. Amsterdam: Faux Titre.

- Lacy, Norris (1987). "The Typology of Arthurian Romance". In Norris J. Lacy, Douglas Kelly, Keith Busby, The Legacy of Chrétien De Troyes vol. I, pp. 33–56. Amsterdam: Faux Titre.

- Mandel, Jerome (1977). "The Ethical Context of Erec's Character". The French Review Volume 50 (3), pp. 421–428.

- Ramey, Lynn Tarte (1993). "Representations of Women in Chrétien's Erec et Enide: Courtly Literature or Misogyny?". Romantic Review vol. 84 (4), pp. 377–386.

- Wittig, Joseph (1970). "The Aeneas-Dido Allusion in Chrétien's Erec et Enide." Comparative Literature Volume 22 (3), pp. 237–253.

Further reading

[edit]- Illingworth, R. N. "STRUCTURAL INTERLACE IN "LI PREMIERS VERS" OF CHRETIEN'S "EREC ET ENIDE"." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 89, no. 3 (1988): 391-405. Accessed June 16, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/43343878.

- "King Arthur’s Justice after the Killing of the White Stag and Iders’s Arrival in Cardigan." In German Romance V: Erec, edited by Edwards Cyril, by Von Aue Hartmann, 58–67. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, NY, USA: Boydell & Brewer, 2014. Accessed June 16, 2020. doi:10.7722/j.ctt6wpbw5.9.

External links

[edit] French Wikisource has original text related to this article: Érec et Énide

French Wikisource has original text related to this article: Érec et Énide- Erec and Enide, English translation in a freely distributable PDF document

Erec and Enide public domain audiobook at LibriVox (English translation)

Erec and Enide public domain audiobook at LibriVox (English translation)