Aelia Capitolina

| |

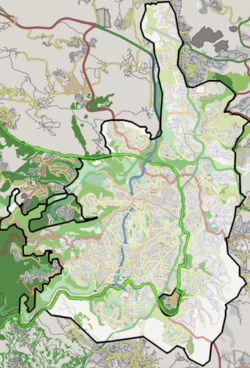

| Location | Jerusalem |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°46′32″N 35°13′52″E / 31.775689°N 35.23104°E |

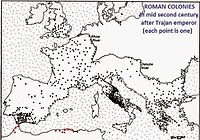

Aelia Capitolina (Latin: Colonia Aelia Capitolina [kɔˈloːni.a ˈae̯li.a kapɪtoːˈliːna]) was a Roman colony founded during the Roman emperor Hadrian's visit to Judaea in 129/130 CE.[1][2] It was founded on the ruins of Jerusalem, which had been almost totally razed after the siege of 70 CE. This act marked a significant transformation of the city from a Jewish metropolis to a small pagan settlement dedicated to the cult of Capitoline Jupiter.[3]

The population of Aelia Capitolina consisted primarily of Roman legionaries, veterans, and other non-Jewish settlers.[3] Jews were forbidden entrance to the city.[2][4] The city's urban layout was redesigned with broad colonnaded streets, arched gateways, and forums that served as commercial and social hubs. The religious landscape also shifted, with the worship of Roman deities replacing the Jewish religious practices that had been centered around the Temple in Jerusalem.[3] Aelia Capitolina remained a relatively minor city within the Roman Empire, with an estimated population of around 4,000 inhabitants, significantly lower than the population during the late Second Temple period.[3]

The modest colony would change dramatically starting in the early 4th century, when Constantine the Great granted Christianity legal status within the Roman Empire. This led to the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, laying the groundwork for its eventual transformation into a prominent Christian center during the Byzantine period.[5] The ban on Jews was maintained until the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem in 636. The Aelia part of the name was used in Arabic as Īlyāʾ during the Umayyad Caliphate.[4]

Name

[edit]Aelia came from Hadrian's Aelia gens, while Capitolina meant that the new city was dedicated to Jupiter Capitolinus,[6] whom the Romans believed had vanquished and replaced the God of the Jews.[7] A temple to Jupiter was built in the city.[6] The Latin name Aelia is the source of the much later term Īlyāʾ (إيليا), a 7th-century early Arab name for Jerusalem.[4]

History

[edit]| Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AD 130 – AD 324–325 | |||

Jerusalem in the Roman empire under Hadrian showing the location of the Roman legions | |||

Chronology

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

Jerusalem, once heavily rebuilt by Herod the Great, was still in ruins following the decisive siege of the city in 70 CE as part of the First Jewish–Roman War.[8]

Emperor Hadrian decided to rebuild the city as a colonia inhabited by his legionaries.[9] Hadrian's new city was to be dedicated to himself and certain Roman gods, in particular Capitoline Jupiter.[10]

Scholars disagree whether Hadrian's anti-Jewish decrees followed the Bar Kokhba revolt or preceded it and were the cause.[11] The older view is that the Bar Kokhba revolt, which took the Romans three years to suppress, enraged Hadrian, and he became determined to erase Judaism from the province. Circumcision was forbidden, and Jews were expelled from the city. Hadrian renamed the province of Judaea to Syria Palaestina, dispensing with the Jewish-associated name.[12]

Jerusalem was renamed Aelia Capitolina[13] and rebuilt in the style of its original Hippodamian plan, although adapted to Roman use. Jews were prohibited from entering the city on pain of death except for one day each year: during the fast day of Tisha B'Av. Taken together, these measures[14][15][16] (which also affected Jewish Christians)[17] essentially secularized the city.[18] Historical sources and archaeological evidence indicate that veterans of the Roman military and immigrants from the western parts of the empire now inhabited the rebuilt city.[19]

Archaeological evidence from this period indicates that Roman customs, including pork consumption and the presence of statues and figured decorations, became widespread. Jewish symbols and practices, such as the use of miqvaot (ritual baths) and traditional stone vessels, disappeared.[3]

According to Eusebius, the Jerusalem church was scattered twice, in 70 and 135, with the difference that from 70 to 130, the bishops of Jerusalem have Jewish names. After 135, the bishops of Aelia Capitolina appear to be Greeks.[20] Eusebius' evidence for the continuation of a church at Aelia Capitolina is confirmed by the Itinerarium Burdigalense.[21]

Plan of the city

[edit]The city was without walls, protected by a light garrison of Legio X Fretensis during the Late Roman period. The detachment at Jerusalem, which encamped all over the city's western hill, was responsible for preventing Jews from returning to the city. Roman enforcement of this prohibition continued through the 4th century.[citation needed]

Layout and street pattern

[edit]The urban plan of Aelia Capitolina was that of a typical Roman town wherein main thoroughfares crisscrossed the urban grid lengthwise and widthwise.[22] The urban grid was based on the usual central north–south road (cardo maximus) and central east–west route (decumanus maximus). However, as the main cardo ran up the western hill, and the Temple Mount blocked the eastward route of the main decumanus, the strict pattern had to be adapted to the local topography; a secondary, eastern cardo, diverged from the western one and ran down the Tyropoeon Valley, while the decumanus had to zigzag around the Temple Mount, passing it on its northern side. The Hadrianic western cardo terminated not far beyond its junction with the decumanus, where it reached the Roman garrison's encampment, but in the Byzantine period, it was extended over the former camp to reach the southern, expanded margins of the city.[citation needed]

The two cardines converged near the Damascus Gate, and a semicircular piazza covered the remaining space; in the piazza, a columnar monument was constructed, hence the Arabic name for the gate, Bab el-Amud ("Gate of the Column"). Tetrapylones were constructed at the other junctions between the main roads.[citation needed]

This street pattern has been preserved in the Old City of Jerusalem to the present. The original thoroughfare, flanked by rows of columns and shops, was about 73 feet (22 meters) wide, but buildings have extended onto the streets over the centuries, and the modern lanes replacing the ancient grid are now quite narrow. The substantial remains of the western cardo have now been exposed to view near the junction with Suq el-Bazaar, and remnants of one of the tetrapylones are preserved in the 19th century Franciscan chapel at the junction of the Via Dolorosa and Suq Khan ez-Zeit.[citation needed]

Western forum

[edit]As was standard for new Roman cities, Hadrian placed the city's main forum at the junction of the main cardo and decumanus, now the location for the (smaller) Muristan. Adjacent to the forum, Hadrian built a large temple to Venus, at a site later used for the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; several boundary walls of Hadrian's temple have been found among the archaeological remains beneath the church.[23]

Valley cardo and eastern forum

[edit]The Struthion Pool lay in the path of the northern decumanus, so Hadrian placed vaulting over it, added a large pavement on top, and turned it into a secondary forum;[24] the pavement can still be seen under the Convent of the Sisters of Zion.[24]

Ecce homo arch

[edit]Near the Struthion Pool, Hadrian built a triple-arched gateway as an entrance to the eastern forum of Aelia Capitolina.[25] Traditionally, this was thought to be the gate of Herod's Antonia Fortress, which itself was alleged to be the location of Jesus' trial and Pontius Pilate's Ecce homo speech as described in John 19:13.[26][27] This was due in part to the 1864 discovery of a game etched on a flagstone of the pool. According to the convent's nuns, the game was played by Roman soldiers[28] and may have ended in the execution of a 'mock king'.[29] Ermete Pierotti is the first to term the words Ecce Homo to the arch, in reference to Pilate's words to Jesus.[30] It is possible that following its destruction, the Antonia Fortress's pavement tiles were brought to the cistern of Hadrian's plaza.[29]

When later constructions narrowed the Via Dolorosa, the two arches on either side of the central arch became incorporated into a succession of more modern buildings. The Basilica of Ecce Homo now preserves the northern arch.[27][31] The southern arch was incorporated into a zawiya (Sufi monastery) for Uzbek dervishes of the Naqshbandi order in the 16th century,[32] but these were demolished in the 19th century in order to found a mosque.[33]

Aftermath

[edit]The reign of Constantine the Great and the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the early fourth century initiated the process of Christian establishment in Jerusalem, eventually transforming the small colony into a prominent Christian center.[5] The city was later ranked the fifth imperial patriarchate, alongside Rome, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Antioch.[5] This transformation continued over the next three centuries during the Byzantine period until the 7th-century Muslim conquest of the city.[5]

The ban against Jews was maintained until the Muslim conquest in 636.[34] Christians had been allowed to visit the city since the 4th century, when Constantine ordered the construction of Christian holy sites in the city. Burial remains from the Byzantine period are exclusively Christian, suggesting that the population of Jerusalem in Byzantine times probably consisted only of Christians.[35]

In the fifth century, the emperor based in Constantinople maintained control of the city, but following Sasanian emperor Khosrow II's early seventh-century advance through Syria, his generals Shahrbaraz and Shahin Vahmanzadegan attacked Jerusalem, aided by the Jews of Palaestina Prima, who had risen against the Byzantines.[36] In 614, after 21 days of siege, Jerusalem was captured. Byzantine chronicles relate that the Sasanian and Jewish forces slaughtered tens of thousands of Christians in the city, many at the Mamilla Pool, and destroyed their monuments and churches, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The conquered city would remain in Sasanian hands for some fifteen years. It was reconquered by emperor Heraclius in 629.[37]

Byzantine Jerusalem was conquered by the armies of Umar, the Rashid caliph, in 636,[38] which resulted in the removal of the restrictions on Jews living in the city. In this era, it was referred to in Arabic as Madinat Bayt al-Maqdis "City of the Temple",[39] a name restricted to the Temple Mount. The rest of the city was called Ilyā, reflecting the Roman name Aelia.[40][a]

See also

[edit]- Alexander of Jerusalem (died 251), bishop of Jerusalem

- Caesarea Maritima, Roman provincial capital after 6 CE

- Gabbatha, biblical name of the place where Pilate tried Jesus

- Names of Jerusalem

References

[edit]Footnotes

Citations

- ^ William E. Metcalf (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage. Oxford University Press. pp. 492–. ISBN 978-0-19-937218-8.

- ^ a b Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah (December 16, 2019). Aelia Capitolina – Jerusalem in the Roman Period: In Light of Archaeological Research. BRILL. pp. 54–58. ISBN 978-90-04-41707-6.

- ^ a b c d e Magness, Jodi (2024). Jerusalem through the ages: from its beginnings to the Crusades. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 338–339. ISBN 978-0-19-093780-5.

- ^ a b c Jacobson, David. "The Enigma of the Name Īliyā (= Aelia) for Jerusalem in Early Islam". Revision 4. Retrieved 2020-12-23.

- ^ a b c d Sivan, Hagith (2008). Palestine in late antiquity. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1, 190, 194–195, 221. ISBN 978-0-19-928417-7. OCLC 170203843.

- ^ a b "Aelia Capitolina". Britannica. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ Magness, Jodi (2024). Jerusalem through the ages: from its beginnings to the Crusades. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-19-093780-5.

- ^ Lohnes, Kate. "Siege of Jerusalem | Facts & Summary". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-06-09.

- ^ Benjamin Isaac, The Near East under Roman Rule: Selected Papers (Leiden: Brill 1998)[page needed]

- ^ Gray, John (1969). A history of Jerusalem. London: Hale. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7091-0364-6. OCLC 53301.

- ^ Peter Schäfer (2003-09-02). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest. Routledge. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-1-134-40316-5.

- ^ Elizabeth Speller, Following Hadrian: A Second-Century Journey Through the Roman Empire, p. 218, at Google Books, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 218

- ^ Lehmann, Clayton Miles. "Palestine: People and Places". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. The University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^ Peter Schäfer (2003). The Bar Kokhba war reconsidered: new perspectives on the second Jewish revolt against Rome. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-3-16-148076-8. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ Lehmann, Clayton Miles (2007-02-22). "Palestine: History". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. The University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 2008-03-10. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^ Cohen, Shaye J. D. (1996). "Judaism to Mishnah: 135–220 AD". In Hershel Shanks (ed.). Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism: A Parallel History of their Origins and Early Development. Washington DC: Biblical Archaeology Society. p. 196.

- ^ Emily Jane Hunt, Christianity in the second century: the case of Tatian, p. 7, at Google Books, Psychology Press, 2003, p. 7

- ^ E. Mary Smallwood The Jews under Roman rule: from Pompey to Diocletian : a study in political relations, p. 460, at Google Books BRILL, 1981, p. 460.

- ^ Klein, Ezra (2010). "The Origins of the Rural Settlers in Judean Mountains and Foothills during the Late Roman Period". In Baruch, E; Levy-Reifer, A; Faust, A (eds.). New Studies on Jerusalem 16. Ramat-Gan. pp. 321–350.

Following the failure of the revolt, the process of the Roman administration's takeover of the city's lands and its surroundings was completed [...] The historical sources confirm that Hadrian gave the city the status of a colony of the citizens of Rome, a title that was awarded almost exclusively to cities where veterans and their families lived. [...] The totality of the data allows us to conclude that a significant component of the population of Ilia Capitolina is the veterans of the Roman army and settlers from the west of the empire.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Jerusalem in Early Christian Thought" p. 75 Explorations in a Christian theology of pilgrimage ed Craig G. Bartholomew, Fred Hughes

- ^ Richard Bauckham "The Christian Community of Aelia Capitolina" in The Book of Acts in Its Palestinian Setting p. 310.

- ^ The Cardo Archived December 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Hebrew University

- ^ Virgilio Corbo, The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (1981)

- ^ a b Benoit, Pierre, The Archaeological Reconstruction of the Antonia Fortress, in Jerusalem Revealed (edited by Yigael Yadin), (1976)

- ^ Benoit, Pierre, The Antonia of Herod the Great, and the East Forum of Aelia Capitolina (1971)

- ^ John 19:13

- ^ a b Warren, E.K.; Hartshorn, W.N.; McCrillis, A.B. (1905). Glimpses of Bible Lands: The Cruise of the Eight Hundred to Jerusalem. Boston, MA: The Central Committee. p. 168.

- ^ Cf. Michael Sebbane (2019), "Board Games from the Eastern Cardo", in Jerusalem: Western Wall Plaza Excavations I: The Roman and Byzantine Remains (IAA Reports 63), p. 153 doi:10.2307/j.ctvpb3vzw.10

- ^ a b "Ecce Homo Arch Video". Jerusalem Experience. 2012.

- ^ Pierotti, Ermete (1864), Jerusalem explored (volume 2), Plate XIII

- ^ Benoit, P. (1971). "L'Antonia D'Hérode le Grand et le Forum Oriental D'Aelia Capitolina". The Harvard Theological Review (in French). 64 (2/3): 135–167. doi:10.1017/S0017816000032478. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1509294. S2CID 162902370.

- ^ Madain Project. "Arch of Hadrian". Retrieved 2019-07-12.

- ^ Lewin, Thomas. The Siege of Jerusalem by Titus: With the Journal of a Recent Visit to the Holy City, and a General Sketch of the Topography of Jerusalem from the Earliest Times Down to the Siege. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1863: 202. Google books. 2019-07-12.

- ^ Zank, Michael. "Byzantian Jerusalem". Boston University. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- ^ Gideon Avni, The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach, p. 144, at Google Books, Oxford University Press 2014 p.144.

- ^ Conybeare, Frederick C. (1910). The Capture of Jerusalem by the Persians in 614 AD. English Historical Review 25. pp. 502–517.

- ^ Rodney Aist,The Christian Topography of Early Islamic Jerusalem,Brepols Publishers, 2009 p.56:'Persian control of Jerusalem lasted from 614 to 629'.

- ^ Dan Bahat (1996). The Illustrated Atlas of Jerusalem. p. 71.

- ^ Ben-Dov, M. Historical Atlas of Jerusalem. Translated by David Louvish. New York: Continuum, 2002, p. 171

- ^ Linquist, J.M., The Temple of Jerusalem, Praeger, London, 2008, p. 184

- ^ "The Name Jerusalem and its History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-12-12.

Bibliography

[edit]- Leo Kadman, The Coins of Aelia Capitolina, Jerusalem, 1956

- Benjamin H. Isaac, Roman Colonies in Judaea: the Foundation of Aelia Capitolina, Talanta XII/XIII (1980/81), pp. 31–54

- Ritti, T., Documenti adrianei da Hierapolis di Frigia: le epistole di Adriano alla città, L’Hellénisme d’époque romaine. Nouveaux documents, nouvelles approches (ier s. a.C.–iiie s. p.C.), Paris, 2014, pp. 297–340

- Yaron Z. Eliav, The Urban Layout of Aelia Capitolina: A New View from the Perspective of the Temple Mount, The Bar Kokhba war reconsidered: new perspectives on the second Jewish Revolt, Peter Schäfer (ed.), 2003, pp. 241–277

- Zissu, B., Klein, E., Kloner, A. Settlement Processes in the territorium of Roman Jerusalem (Aelia Capitolina), J. M. Alvarez, T. Nogales, I. Roda (hg.), XVIII CIAC: Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World, Mérida, 2014, pp. 219–223.

- S. Weksler-Bdolah, The Foundation of Aelia Capitolina in Light of New Excavations along the Eastern Cardo, IEJ 64, 2014, pp. 38–62

- B. Isaac,Caesarea-on-the-Sea and Aelia Capitolina: Two Ambiguous Roman Colonies, L’héritage Grec des colonies Romaines d’Orient. Interactions culturelles dans les provinces hellénophones de l’empire romain, C. Brélaz (hg.), Paris, 2017, pp. 331–343.

- Kloner, A., Klein, E., Zissu, B., The Rural Hinterland (territorium) of Aelia Capitolina, G. Avni, G. D. Stiebel (hg.), Roman Jerusalem: A New Old City, Portsmouth, RI, 2017, pp. 131–141.

- Newman, H. I., The Temple Mount of Jerusalem and the Capitolium of Aelia Capitolina, Knowledge and Wisdom: Archaeological and Historical Essays in Honour of Leah Di Segni, G. C. Bottini, L. D. Chrupcała, J. Patrich (hg.), Jerusalem, 2017, pp. 35–42

- A. Bernini, Un riconoscimento di debito redatto a Colonia Aelia Capitolina, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 206, 2018, pp. 183–193

- A. Bernini, New Evidence for Colonia Aelia Capitolina (P. Mich. VII 445 + inv. 3888c + inv. 3944k, Proceedings of the 28th International Congress of Papyrology, Barcelona, 2019, pp. 557–562.

- Werner Eck, Die Colonia Aelia Capitolina: Überlegungen zur Anfangsphase der zweiten römischen Kolonie in der Provinz Iudaea-Syria Palaestina, ELECTRUM, Vol. 26 (2019), pp. 129–139

- Miriam Ben Zeev Hofman, Eusebius and Hadrian's Founding of Aelia Capitolina in Jerusalem, ELECTRUM, Vol. 26 (2019), pp. 119–128

- Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah, Aelia Capitolina – Jerusalem in the Roman Period - In Light of Archaeological Research, Mnemosyne, Supplements, History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity, Volume: 432, Brill, 2020

External links

[edit]- Detailed description (including map) of the city of Aelia Capitolina Archived 2021-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Pictures of the cave where it is believed by Christians that Jesus was buried and from which it is believed he resurrected and a picture of the remains of the walls of the Temple of Venus previously constructed on that site by the emperor Hadrian

- "Archaeologists bringing Jerusalem's ancient Roman city back to life" by Nir Hasson, Ha'aretz, February 21, 2012

- Photos of the Ecco Homo Arch at the Manar al-Athar photo archive

- Jews and Judaism in the Roman Empire

- Classical sites in Jerusalem

- Former populated places in West Asia

- Ancient history of Jerusalem

- Judea (Roman province)

- Nerva–Antonine dynasty

- Populated places established in the 2nd century

- 131 establishments

- 130s establishments in the Roman Empire

- 320s disestablishments in the Roman Empire

- Roman towns and cities in Israel

- Coloniae (Roman)

- State of Palestine in the Roman era

- Old City (Jerusalem)