Ted Kaczynski: Difference between revisions

Reverted 1 pending edit by 94.197.121.56 to revision 797432725 by EEng: Unsourced |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{Original research|discuss=Talk:Ted Kaczynski#Original research discussion|date=July 2017}} |

{{Original research|discuss=Talk:Ted Kaczynski#Original research discussion|date=July 2017}} |

||

{{Infobox criminal |

{{Infobox criminal |

||

| name = Ted Kaczynski |

| name = Dr Ted Kaczynski |

||

| image_name = Theodore Kaczynski.jpg{{!}}border |

| image_name = Theodore Kaczynski.jpg{{!}}border |

||

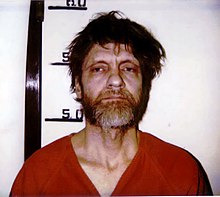

| image_caption = Kaczynski after his capture by police, 1996 |

| image_caption = Kaczynski after his capture by police, 1996 |

||

Revision as of 23:28, 29 August 2017

This article possibly contains original research. (July 2017) |

Dr Ted Kaczynski | |

|---|---|

Kaczynski after his capture by police, 1996 | |

| Born | Theodore John Kaczynski May 22, 1942 |

| Other names | The Unabomber |

| Education | Harvard University (1958–62) University of Michigan (1962–67) |

| Occupation | Mathematician |

| Notable work | Industrial Society and Its Future (1995) |

| Criminal status | Incarcerated at ADX Florence, #04475–046[1] |

| Conviction(s) | 10 counts of transportation, mailing and use of bombs; 3 counts of murder |

| Criminal penalty | 8 consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole |

| Details | |

Span of crimes | 1978–1995 |

| Killed | 3 |

| Injured | 23 |

Date apprehended | April 3, 1996 |

Theodore John Kaczynski (/kəˈzɪnski/; born May 22, 1942), also known as the Unabomber, is an American mathematician, anarchist and domestic terrorist.[2] A mathematical prodigy, he abandoned a promising academic career in 1969, then between 1978 and 1995 killed 3 people, and injured 23 others, in a nationwide bombing campaign that targeted people involved with modern technology. In conjunction with the bombing campaign, he issued a wide-ranging social critique opposing industrialization and advancing a nature-centered form of anarchism.[3][4][5]

Raised in Evergreen Park, Illinois, Kaczynski was a child prodigy and accepted into Harvard University at the age of 16. He earned his B.A. from Harvard in 1962, then his M.A. and Ph.D in mathematics from the University of Michigan in 1965 and 1967, respectively. After receiving his doctorate at age 25, he became an assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley but resigned abruptly two years later.[6] As an undergraduate at Harvard, Kaczynski was a research subject in an ethically questionable experiment conducted by psychology professor Henry Murray, which some analysts have suggested influenced Kaczynski's later actions.[7][8][9]

In 1971, he moved to a remote cabin without electricity or running water in Lincoln, Montana, where he lived as a recluse while learning survival skills in an attempt to become self-sufficient.[10] In 1978, after witnessing the destruction of the wildland surrounding his cabin, he concluded that living in nature was untenable and began his bombing campaign. In 1995, Kaczynski sent a letter to The New York Times and promised to "desist from terrorism" if the Times or The Washington Post published his manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future, in which he argued that his bombings were extreme but necessary to attract attention to the erosion of human freedom and dignity by modern technologies that require large-scale organization.

Kaczynski was the target of the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) longest and costliest investigation.[11] Before his identity was known, the FBI used the title "UNABOM" (UNiversity & Airline BOMber) to refer to his case, which resulted in the media calling him the Unabomber. The FBI (as well as Attorney General Janet Reno) pushed for the publication of Kaczynski's manifesto, which led to his sister-in-law, and then his brother, recognizing Kaczynski's style of writing and beliefs from the manifesto, and tipping off the FBI.[12] After his arrest in 1996, Kaczynski tried unsuccessfully to dismiss his court-appointed lawyers because they wanted to plead insanity in order to avoid the death penalty, as Kaczynski did not believe he was insane.[13] On January 22, 1998, when it became clear that his trial would entail national television exposure, the court entered a plea agreement, under which Kaczynski pleaded guilty to all charges and was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Childhood

Kaczynski was born on May 22, 1942 in Chicago, Illinois to working-class, second-generation Polish Americans, Wanda Theresa (née Dombek) and Theodore Richard Kaczynski, who lived on Carpenter Street, Chicago.[14] At nine months of age, Kaczynski suffered a severe allergic reaction and developed hives, which caused him to be placed in isolation in a hospital where visitors were allowed limited contact. According to his younger brother David, who was told the story by his parents, Ted was a happy baby but after he came home from the hospital he "showed little emotion for months".[15] Wanda wrote in March 1943, "Baby home from hospital and is healthy but quite unresponsive after his experience."[16] Wanda also later recalled an incident when Ted recoiled in fright after he was shown a picture of himself as an infant being held down by physicians while they took photographs of his hives, and stated that Ted always showed sympathy to animals in cages or other helpless positions, which she speculated was due to his experience in isolation as an infant.[17]

From grades one through four, Kaczynski attended Sherman Elementary School in Chicago, where administrators described him as "healthy" and "well-adjusted". He then attended grades five through eight at Evergreen Park Central School. Testing conducted in the fifth grade scored his IQ at 167.[18] As a result, he was allowed to skip the sixth grade and enroll in the seventh grade. Kaczynski described this as a pivotal event in his life. Before then, he regularly socialized with his peers and even took on leadership roles but after skipping ahead, he recalled not fitting in with the older children and being subjected to their bullying.[19]

In 1952, three years after Ted's brother David was born, Wanda and Theodore moved the family to a three-bedroom, Cape Cod style home at 9209 S. Lawndale in southwest suburban Evergreen Park, Illinois. Their neighbors there later described the Kaczynski family as "civic-minded folks", with one stating that Wanda and Theodore "really sacrificed everything they had for their children".[15] Both Ted and David were intelligent, but Ted stood out in particular due to his intelligence. Evelyn Vanderlaan, a fellow Evergreen Park resident, stated she had "never known anyone who had a brain like [Ted] did,"[20] while another neighbor, Dr. Roy Weinberg, commented that Ted was "strictly a loner" who "didn't play" and was "an old man before his time."[15] After his arrest in 1996, Wanda recalled that Ted was extremely shy as a child and would become unresponsive if pressured into a social situation.[21] At one point, she was so worried by Ted's social development that she considered entering him in a study for autistic children led by Bruno Bettelheim, but decided against putting him through the study after being discouraged by the doctor's abrupt and cold manner in the classroom.[22]

Education

Kaczynski attended Evergreen Park Community High School. He excelled academically, played the trombone in the marching band and was a member of the math club, biology club, coin club and German club but was regarded as an outsider by his classmates.[23][24] In 1996, Loren DeYoung, one of his former classmates, said: "[Kaczynski] was never really seen as a person, as an individual personality ... He was always regarded as a walking brain, so to speak."[15] During this period of his life, Kaczynski became obsessed with mathematics and spent prolonged hours alone in his room practicing differential equations. Due to this, he became associated with a group of likeminded boys interested in science and mathematics, known as the "briefcase boys" due to their penchant for carrying their textbooks in briefcases.[24] Russell Mosny, a member of this group, later stated Kaczynski was "the smartest kid in the class," and he was "just quiet and shy until you got to know him. Once he knew you, he could talk and talk."[15]

Throughout high school, Kaczynski was ahead of his classmates, and able to solve advanced Laplace transforms by his junior year. He was subsequently placed in a more advanced mathematics class, yet still felt intellectually restricted. Kaczynski soon mastered the material, allowing him to skip the eleventh grade. He then enrolled in a summer school English course to complete his high school education at the age of 15. He was one of Evergreen Park Community High School's five National Merit Scholarship Program finalists, and encouraged to apply to Harvard University.[23] He was accepted as a student and granted a scholarship, beginning in 1958 at the age of 16.[25] High school classmate Russell Mosny later said that Kaczynski was unprepared to attend the university, stating: "They packed him up and sent him to Harvard before he was ready. ... He didn't even have a driver's license."[15]

At Harvard, Kaczynski spent his first year in student housing on 8 Prescott Street, which was designed to accommodate the youngest, most precocious freshmen in a small, intimate living space. He moved to Eliot House the next year, where he remained for the rest of his time at the university. One of his Eliot House suitemates, Patrick McIntosh, later stated that Kaczynski avoided contact with others and when entering "would just rush through the suite, go into his room, and slam the door." Another suitemate, Wayne B. Persons, also said Kacyznski was reserved but regarded him as a genius: "It's just an opinion—but Ted was brilliant." Other students stated Kaczynski was less socially averse than his suitemates' descriptions; John V. Federico, a fellow Eliot House resident, recalled sitting with Kaczynski in the dining hall on a number of occasions and stated he was "very quiet, but personable ... He would enter into the discussions maybe a little less so than most [but] he was certainly friendly."[26]

In his sophomore year at Harvard, Kaczynski participated in a personality assessment study that was conducted by Harvard psychologists and led by Henry Murray. Students in Murray's study were told they would be debating personal philosophy with a fellow student. Instead, they were subjected to "vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive" attacks in a "purposely brutalizing psychological experiment".[27] During the test, students were taken into a room and connected to electrodes that monitored their physiological reactions, while facing bright lights and a one-way mirror. Each student had previously written an essay detailing their personal beliefs and aspirations: the essays were turned over to an anonymous attorney, who would enter the room and individually belittle each student based in part on the disclosures they had made. This was filmed, and students' expressions of impotent rage were played back to them several times later in the study. According to author Alston Chase, Kaczynski's records from that period suggest he was emotionally stable when the study began, and Kaczynski's lawyers would later attribute his deep-seated hostility towards mind control techniques to his participation in this study.[27] Furthermore, some have suggested that this experience may have been instrumental in Kaczynski's future actions.[28][29]

Kaczynski earned his Bachelor of Arts in mathematics from Harvard in 1962. In his senior year, he scored a B in Math 210, B in Math 250, B+ in History of Science, B- in Humanities 115, A- in Anthropology 122, C+ in History 143 and A- in Scandinavian, and finished with a 3.12 GPA. These grades were above-average, but Kaczynski was expected to perform better due to his prodigious status upon entering the university.[30]

Mathematical career

After he graduated from Harvard University in 1962, Kaczynski enrolled at the University of Michigan, where he earned his Master of Arts and Doctor of Philosophy in mathematics in 1965 and 1967, respectively. The University of Michigan was not his first choice for graduate work; in addition to the University of Michigan, he also applied to the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Chicago. Both schools accepted him, but neither offered a student-teaching position or financial aid. The University of Michigan offered him an annual grant of $2,310 (equivalent to $18,700 in 2017) and a position in the mathematics faculty as a student-teacher.[30]

At the University of Michigan, Kaczynski specialized in complex analysis, specifically geometric function theory. His intellect and drive impressed his professors at Michigan. "He was an unusual person. He was not like the other graduate students. He was much more focused about his work. He had a drive to discover mathematical truth," said Peter Duren, one of Kaczynski's math professors. "It is not enough to say he was smart," said George Piranian, another of his Michigan math professors.[31] During his time at Michigan, Kaczynski scored 5 B's and 12 A's in his 18 courses. However in a 2006 correspondence, he said his "memories of the University of Michigan are NOT pleasant" and stated "the fact that I not only passed my courses (except one physics course) but got quite a few A's, shows how wretchedly low the standards were at Michigan."[30]

Kaczynski's doctoral thesis was entitled "Boundary Functions".[32] Regarding the thesis, Kaczynski's doctoral advisor Allen Shields stated it was "the best I have ever directed".[30] Maxwell Reade, a retired math professor who served on Kaczynski's dissertation committee, also commented on the thesis by noting, "I would guess that maybe 10 or 12 men in the country understood or appreciated it."[31][15] In 1967, Kaczynski won the University of Michigan's Sumner B. Myers Prize, which recognized his dissertation as the school's best in mathematics that year.[15] He also published two articles related to his dissertation in mathematical journals, and three more after leaving Michigan.[32][33]

In late 1967, Kaczynski, at age 25, became an assistant professor of mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught undergraduate courses in geometry and calculus. This appointment made him the youngest math professor ever hired by the university.[34] Student questionnaires from the time suggest that Kaczynski was not well-liked by the undergraduates he taught; students stated that he seemed uncomfortable in a teaching environment, taught straight from the textbook and, despite a small class size, "absolutely refuse[d] to answer questions."[15] Without explanation, Kaczynski resigned from his position on June 30, 1969.[35] At the time, the chairman of the mathematics department, J. W. Addison, called this a "sudden and unexpected" resignation.[36][37] In 1996, vice chairman Calvin C. Moore said that, given Kaczynski's "impressive" thesis and record of publications, he "could have advanced up the ranks and been a senior member of the faculty today."[38]

Published works

During his career as a mathematician, Kaczynski published the following mathematical works:

| Title | Journal, or Source | Publication Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Another Proof of Wedderburn's Theorem.[39] | American Mathematical Monthly, 71, 652-653. | June–July 1964. | A proof of Wedderburn's little theorem, a theorem in abstract algebra. |

| Advanced Problem 5210.[40] | Ibid, 689. | June–July 1964. | A challenge problem in abstract algebra. The problem was reprinted and solved in the following citation. |

| Distributivity and (-1)x = -x (Advanced Problem 5210, with Solution by Bilyeu, R.G.).[41] | American Mathematical Monthly, 72, 677-678. | June–July 1965. | See above. |

| Boundary Functions for Functions Defined in a Disk.[42] | Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics, 14, 589-612. | 1965. | A technical paper relating to Kaczynski's research interest in boundary functions. |

| On a Boundary Property of Continuous Functions.[43] | Michigan Mathematical Journal, 13, 313-320. | November 1966. | See above. |

| Boundary Functions.[44] | Doctoral dissertation. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. | 1967. | Kaczynski's doctoral dissertation. |

| Note on a Problem of Alan Sutcliffe.[45] | Mathematics Magazine, 41(2), 84-86. | March–April 1968. | A brief paper in number theory concerning the digits of numbers. |

| Boundary Functions for Bounded Harmonic Functions.[46] | Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 137, 203-209. | March 1969. | A technical paper relating to Kaczynski's research interest in boundary functions. |

| Boundary Functions and Sets of Curvilinear Convergence for Continuous Functions.[47] | Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 141, 107-125. | July 1969. | See above. |

| The Set of Curvilinear Convergence of a Continuous Function Defined in the Interior of a Cube.[48] | Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 23(2), 323-327. | November 1969. | See above. |

| Problem 787.[49] | Mathematics Magazine, 44(1), 41. | January–February 1971. | A challenge problem in geometry. The problem was reprinted and solved in the following citation. |

| A Match Stick Problem (Problem 787, with Solutions by Gibbs, R.A. and Breisch, R.L.).[50] | Mathematics Magazine, 44, 294-296. | November–December 1971. | See above. |

Boundary Functions for Functions Defined in a Disk should not be confused with an earlier article, co-authored by Kaczynski's professor George Piranian (but which Kaczynski did not contribute to), which has the same title.[51] Kaczynski cited this earlier article in his own later piece of the same name.

Although Kaczynski produced a large amount of material during this period, his work has had limited impact on subsequent mathematics. While Kaczynski cited his own work on multiple occasions (common for an academic), only a small number of authors other than Kaczynski have cited him in their own works.[52][53][54] A Los Angeles Times article published after Kaczynski's capture in 1996 stated that the "field that Kaczynski worked in doesn't really exist today, ... Most of its theories were proven in the 1960s, when Kaczynski worked on it." According to mathematician Donald Rung, "[Kaczynski] probably would have gone on to some other area if he were to stay in mathematics."[35]

Move to Montana

After resigning from the University of California, Berkeley, Kaczynski moved into his parents' small residence in Lombard, Illinois. Two years later, he moved to a remote cabin he had built himself just outside Lincoln, Montana, where he lived a simple life on very little money, without electricity or running water.[55] During this time, Kaczynski worked odd jobs and received financial support from his family, which he used to purchase his land and, without their knowledge, would later use to fund his bombing campaign.[15]

Kaczynski's original goal was to move out to a secluded area and become self-sufficient so that he could live autonomously. He began to teach himself survival skills such as tracking game, edible plant identification, organic farming and construction of primitive technologies (e.g. bow drills).[10] Fellow Lincoln residents stated that Kaczynski's reclusive lifestyle was not unusual, and that they were shocked by his arrest. He used an old bicycle to get to town. A volunteer at the local library said he visited frequently and read classic works in their original languages.[56]

Despite some success at living autonomously, Kaczynski decided it was impossible to live peacefully in nature after witnessing the continual destruction of the wildland around his cabin by real estate development and industrial projects.[10] In response, he initially performed isolated acts of sabotage which targeted the developments near his cabin, but soon also began his bombing campaign. Regarding the motive for his bombing campaign, Kaczynski recalled an incident when he went out on a hike to one of his favorite wild spots, only to find that it had been destroyed and replaced with a road. About this, he said:

The best place, to me, was the largest remnant of this plateau that dates from the tertiary age. It's kind of rolling country, not flat, and when you get to the edge of it you find these ravines that cut very steeply in to cliff-like drop-offs and there was even a waterfall there. It was about a two days' hike from my cabin. That was the best spot until the summer of 1983. That summer there were too many people around my cabin so I decided I needed some peace. I went back to the plateau and when I got there I found they had put a road right through the middle of it... You just can't imagine how upset I was. It was from that point on I decided that, rather than trying to acquire further wilderness skills, I would work on getting back at the system. Revenge.[10]

He began dedicating himself to reading about sociology and books on political philosophy, such as the works of Jacques Ellul, and also stepped up his campaign of sabotage. He soon came to the conclusion that more violent methods would be the only solution to what he saw as the inherent problems of industrial civilization. In a 1999 interview, he stated that during this time he lost faith in the idea of reform, and saw violent collapse as the only way to bring down the industrial-technological system.[10] Regarding his switch from being a reformer of the system to developing a means of taking it down, he said:

I don't think it can be done. In part because of the human tendency, for most people, there are exceptions, to take the path of least resistance. They'll take the easy way out, and giving up your car, your television set, your electricity, is not the path of least resistance for most people. As I see it, I don't think there is any controlled or planned way in which we can dismantle the industrial system. I think that the only way we will get rid of it is if it breaks down and collapses... The big problem is that people don't believe a revolution is possible, and it is not possible precisely because they do not believe it is possible. To a large extent I think the eco-anarchist movement is accomplishing a great deal, but I think they could do it better... The real revolutionaries should separate themselves from the reformers... And I think that it would be good if a conscious effort was being made to get as many people as possible introduced to the wilderness. In a general way, I think what has to be done is not to try and convince or persuade the majority of people that we are right, as much as try to increase tensions in society to the point where things start to break down. To create a situation where people get uncomfortable enough that they're going to rebel. So the question is how do you increase those tensions?[10]

Bombings

Between 1978 and 1995, Kaczynski mailed or hand-delivered a series of increasingly sophisticated bombs that ultimately killed 3 people and injured 23. He took extreme care during the preparation of the bombs to avoid leaving fingerprints, and purposefully left misleading clues in the bombs.

Initial bombings

Kaczynski's first mail bomb was directed at Buckley Crist, a professor of materials engineering at Northwestern University. On May 25, 1978 the package was apparently left in a parking lot at the University of Illinois at Chicago, bearing Crist's return address. The package accordingly "returned" to Crist but Crist, suspicious of a package he had not sent, contacted campus police. Officer Terry Marker opened the package, which exploded immediately and injured Marker's left hand.[57]

The bomb was made of metal that could have come from a home workshop. The primary component was a piece of metal pipe, about 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter and 9 inches (23 cm) long. The bomb contained smokeless explosive powders, and the box and the plugs that sealed the pipe ends were handcrafted from wood. In comparison, most pipe bombs usually use threaded metal ends sold in many hardware stores. Wooden ends lack the strength to allow significant pressure to build within the pipe, explaining why the bomb did not cause severe damage. The primitive trigger device that the bomb employed was a nail, tensioned by rubber bands designed to slam into six common match heads when the box was opened. The match heads would burst into flame and ignite the explosive powders. When the trigger hit the match heads, only three ignited. A more efficient technique, later employed by Kaczynski, was to use batteries and heat filament wire to ignite the explosives faster and more effectively.[58]

Kaczynski had returned to Illinois for the May 1978 bombing, and stayed there for a time to work with his father and brother at a foam rubber factory. However, in August 1978, he was fired by his brother for writing insulting limericks about a female supervisor who he had briefly dated.[59][60] The supervisor later recalled Kaczynski as "intelligent, quiet" but remembered little of their acquaintance; she firmly denied they had had any romantic relationship.[61]

The initial 1978 bombing was followed by bombs sent to airline officials, and in 1979, a bomb was placed in the cargo hold of American Airlines Flight 444, a Boeing 727 flying from Chicago to Washington, D.C. A faulty timing mechanism prevented the bomb from exploding, but it released smoke which forced an emergency landing. Authorities said it had enough power to "obliterate the plane" had it exploded.[57] As bombing an airliner is a federal crime, the Federal Bureau of Investigation became involved in the case, designating it UNABOM, for UNiversity and Airline BOMber. (U.S. Postal Inspectors, who initially had the case, labeled the suspect the "Junkyard Bomber" because of the material used to make the mail bombs.)[62] In 1979, an FBI-led task force that included the ATF and U.S. Postal Inspection Service was formed. The task force grew to more than 150 full-time personnel, but minute analysis of recovered components of the bombs, and investigation of the lives of victims, proved of little use in identifying the suspect, who built his bombs primarily from scrap materials available almost anywhere. The victims, investigators later learned, were chosen irregularly from library research.

In 1980, chief agent John Douglas, working with agents in the FBI's Behavioral Sciences Unit, issued a psychological profile of the unidentified bomber which described the offender as a man with above-average intelligence with connections to academia. This profile was later refined to characterize the offender as a neo-Luddite holding an academic degree in the hard sciences, but this psychologically based profile was discarded in 1983 in favor of an alternative theory developed by FBI analysts concentrating on the physical evidence in recovered bomb fragments. In this rival profile, the bomber suspect was characterized as a blue-collar airplane mechanic.[63] A 1-800 hotline was set up by the UNABOM Task Force to take any calls related to the Unabomber investigation, with a $1 million reward for anyone who could provide information leading to the Unabomber's capture.[64]

Casualties

The first serious injury occurred in 1985, when John Hauser, a graduate student and captain in the United States Air Force, lost four fingers and vision in one eye.[65] The bomb, like others of Kaczynski's, was handcrafted and made with wooden parts.[66]

Hugh Scrutton, a 38-year-old Sacramento, California computer store owner, was killed in 1985 by a nail-and-splinter-loaded bomb placed in the parking lot of his store. A similar attack against a computer store occurred in Salt Lake City, Utah on February 20, 1987. The bomb, which was disguised as a piece of lumber, injured Gary Wright when he attempted to remove it from the store's parking lot. The explosion severed nerves in Wright's left arm and propelled more than 200 pieces of shrapnel into his body. Kaczynski's brother, David—who would play a vital role in Kaczynski's capture by alerting federal authorities to the prospect of his brother's involvement in the Unabomber cases—sought out and became friends with Wright after Kaczynski was detained in 1996. David Kaczynski and Wright have remained friends and occasionally speak together publicly about their relationship.[67]

After a six-year break, Kaczynski struck again in 1993, mailing a bomb to David Gelernter, a computer science professor at Yale University. Though critically injured, Gelernter eventually recovered. Another bomb mailed in the same weekend was sent to the home of Charles Epstein from the University of California, San Francisco, who lost several fingers upon opening it. Kaczynski then called Gelernter's brother, Joel Gelernter, a behavioral geneticist, and told him, "You are next."[68] Geneticist Phillip Sharp at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology also received a threatening letter two years later.[69]

In 1994, Burson-Marsteller executive Thomas J. Mosser was killed by a mail bomb sent to his North Caldwell, New Jersey home. In another letter to The New York Times, Kaczynski claimed that he "blew up Thomas Mosser because ... Burston-Marsteller helped Exxon clean up its public image after the Exxon Valdez incident" and, more importantly, because "its business is the development of techniques for manipulating people's attitudes."[70] This was followed by the 1995 murder of Gilbert Brent Murray, president of the timber industry lobbying group California Forestry Association, by a mail bomb addressed to previous president William Dennison, who had retired.[69]

In all, 16 bombs—which injured 23 people and killed 3—were attributed to Kaczynski. While the devices varied widely through the years, all but the first few contained the initials "FC." Inside his bombs, certain parts carried the inscription "FC," which Kaczynski later asserted stood for "Freedom Club."[71][71] Latent fingerprints on some of the devices did not match the fingerprints found on letters attributed to Kaczynski. As stated in the "Additional Findings" section of the FBI affidavit (where a balanced listing of other uncorrelated evidence and contrary determinations also appeared):

203. Latent fingerprints attributable to devices mailed and/or placed by the UNABOM subject were compared to those found on the letters attributed to Theodore Kaczynski. According to the FBI Laboratory no forensic correlation exists between those samples.[72]

One of Kaczynski's tactics was leaving false clues in every bomb. He would deliberately make them hard to find to mislead investigators into thinking they had a clue. The first clue was a metal plate stamped with the initials "FC" hidden somewhere (usually in the pipe end cap) in every bomb.[72] One false clue he left was a note in a bomb that did not detonate which reads "Wu—It works! I told you it would—RV".[73] Another clue was the Eugene O'Neill $1 stamps used to send his boxes.[74] One of his bombs was sent embedded in a copy of Sloan Wilson's novel Ice Brothers.[57]

The FBI theorized that Kaczynski had a theme of nature, trees and wood in his crimes. He often included bits of tree branch and bark in his bombs. Targets selected included Percy Wood, Professor Leroy Wood Bearson and Thomas Mosser. Crime writer Robert Graysmith noted, "in the Unabomber's case a large factor was his obsession with wood."[75]

List of bombings

| Date | Location | Victim(s) | Injuries |

|---|---|---|---|

| May 25, 1978 | Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois | Terry Marker, university police officer | Minor cuts and burns |

| May 9, 1979 | Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois | John Harris, graduate student | Minor cuts and burns |

| November 15, 1979 | American Airlines Flight 444 from Chicago to Washington, DC (explosion occurred in midflight) | Twelve passengers | Non-lethal smoke inhalation |

| June 10, 1980 | Lake Forest, Illinois | Percy Wood, president of United Airlines | Cuts and burns over most of body and face |

| October 8, 1981 | University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah | None, bomb successfully defused | None |

| May 5, 1982 | Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee | Janet Smith, university secretary | Severe burns to hands and shrapnel wounds to body |

| July 2, 1982 | University of California, Berkeley | Diogenes Angelakos, engineering professor | Severe burns and shrapnel wounds to right hand and face |

| May 15, 1985 | University of California, Berkeley | John Hauser, graduate student | Loss of four fingers on right hand and severed artery in right arm, partial loss of vision in left eye |

| June 13, 1985 | The Boeing Company in Auburn, Washington | None, bomb successfully defused | None |

| November 15, 1985 | University of Michigan, Ann Arbor | James V. McConnell, psychology professor, and Nicklaus Suino, research assistant | McConnell: temporary hearing loss; Suino: burns and shrapnel wounds |

| December 11, 1985 | Sacramento, California | Hugh Scrutton, computer store owner | Death (first fatality) |

| February 20, 1987 | Salt Lake City, Utah | Gary Wright, computer store owner | Severe nerve damage to left arm |

| June 22, 1993 | Tiburon, California | Charles Epstein, geneticist | Severe damage to both eardrums resulting in partial hearing loss, loss of three fingers |

| June 24, 1993 | Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut | David Gelernter, computer science professor | Severe burns and shrapnel wounds, permanent damage to right eye and loss of right hand. |

| December 10, 1994 | North Caldwell, New Jersey | Thomas J. Mosser, advertising executive | Death (second fatality) |

| April 24, 1995 | Sacramento, California | Gilbert Brent Murray, timber industry lobbyist | Death (third fatality) |

| References:[76][77] | |||

Industrial Society and Its Future

In 1995, Kaczynski mailed several letters to media outlets outlining his goals and demanding that his 35,000-word essay Industrial Society and Its Future, referred to as the Unabomber Manifesto by the FBI,[78] be printed verbatim by a major newspaper. He stated that if this demand was met, he would then "desist from terrorism".[79][80][81]

There was controversy as to whether the document should be published, but the Department of Justice headed by Attorney General Janet Reno, along with FBI Director Louis Freeh, recommended publication out of concern for public safety and in hopes that a reader could identify the author. Bob Guccione of Penthouse volunteered to publish it, but Kaczynski replied that, since Penthouse was less "respectable" than the other publications, he would in that case "reserve the right to plant one (and only one) bomb intended to kill, after our manuscript has been published."[82] The pamphlet was published by The New York Times and The Washington Post on September 19, 1995.[83][84] Penthouse never published it.[85]

Throughout the document, produced on a typewriter without the capacity for italics, Kaczynski capitalizes entire words in order to show emphasis. He always refers to himself as either "we" or "FC" (Freedom Club), though there is no evidence that he worked with others. Donald Foster, who analyzed the writing at the request of Kaczynski's defense, noted that the document contains instances of irregular spelling and hyphenation, as well as other linguistic idiosyncrasies, which led him to conclude that it was Kaczynski who wrote it.[86]

Summary

This section possibly contains original research. (July 2017) |

Industrial Society and Its Future begins with Kaczynski's assertion that "[t]he Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race."[87][88]

Kaczynski states that technology has had a destabilizing effect on society, has made life unfulfilling and has caused widespread psychological suffering.[89] He argues that because of technological advances, most people spend their time engaged in useless pursuits which he calls "surrogate activities", wherein people strive towards artificial goals. Examples he gives of artificial goals include scientific work, consumption of entertainment and following sports teams.[89] He predicts that further technological advances will lead to extensive human genetic engineering and that human beings will be adjusted to meet the needs of the social systems, rather than vice versa.[89] He believes that technological progress can be stopped, unlike others who he says understand some of its negative effects yet passively accept it as inevitable,[90] and calls for a return to "wild nature".[89]

Kaczynski argues that erosion of human freedom is a natural product of industrial society because "[t]he system has to regulate human behavior closely in order to function," and that reform of the system is impossible as "[c]hanges large enough to make a lasting difference in favor of freedom would not be initiated because it would be realized that they would gravely disrupt the system."[91] However, he states that the system has not yet fully achieved "control over human behavior" and "is currently engaged in a desperate struggle to overcome certain problems that threaten its survival." He predicts that "[i]f the system succeeds in acquiring sufficient control over human behavior quickly enough, it will probably survive. Otherwise it will break down," and that "the issue will most likely be resolved within the next several decades, say 40 to 100 years."[91] Kaczynski therefore states that the task of those who oppose industrial society is to promote "social stress and instability," and to propagate "an ideology that opposes technology," one that offers the "counter-ideal" of nature "in order to gain enthusiastic support." Thus, when industrial society is sufficiently unstable, "a revolution against technology may be possible."[92]

Throughout the document, Kaczynski addresses leftism as a movement. He defines leftists as "mainly socialists, collectivists, 'politically correct' types, feminists, gay and disability activists, animal rights activists and the like,"[93] states that leftism is driven primarily by "feelings of inferiority" and "oversocialization,"[89] and derides leftism as "one of the most widespread manifestations of the craziness of our world."[93] Kaczynski additionally states that "a movement that exalts nature and opposes technology must take a resolutely anti-leftist stance and must avoid all collaboration with leftists", as in his view "[l]eftism is in the long run inconsistent with wild nature, with human freedom and with the elimination of modern technology".[87] He also criticizes conservatives, describing them as "fools" who "whine about the decay of traditional values, yet they enthusiastically support technological progress and economic growth. Apparently it never occurs to them that you can't make rapid, drastic changes in the technology and the economy of a society without causing rapid changes in all other aspects of the society as well, and that such rapid changes inevitably break down traditional values."[93]

Reception

In The Atlantic, Alston Chase reported that the text "was greeted in 1995 by many thoughtful people as a work of genius, or at least profundity, and as quite sane."[94] Chase himself argued, however, that it "is the work of neither a genius nor a maniac. […] Its pessimism over the direction of civilization and its rejection of the modern world are shared especially with the country's most highly educated."[94]

UCLA professor James Q. Wilson, who was mentioned in the manifesto, wrote for The New Yorker that Industrial Society and Its Future was "a carefully reasoned, artfully written paper ... If it is the work of a madman, then the writings of many political philosophers — Jean Jacques Rousseau, Tom Paine, Karl Marx — are scarcely more sane."[95]

David Skrbina, a philosophy professor at the University of Michigan and a former Green Party candidate for the governor of Michigan, has written several essays in support of investigating the Unabomber's ideas, one of which he entitled "A Revolutionary for Our Times."[96][97][98]

Paul Kingsnorth, a former deputy-editor of The Ecologist and a co-founder of the Dark Mountain Project, wrote an essay for Orion Magazine in which he described Kaczynski's arguments as "worryingly convincing" and stated that they "may change my life."[99]

Keith Ablow, writing for Fox News, stated that Kaczynski was "reprehensible for murdering and maiming people" but "precisely correct in many of his ideas," and compared Industrial Society and Its Future to Aldous Huxley's Brave New World and George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.[100]

Some anarcho-primitivist authors, such as John Zerzan and John Moore, came to Kaczynski's defense, while also holding certain reservations about his actions and ideas.[101][102]

Other published works

Kaczynski has carried on a prolific and meticulous research, writing, and correspondence regimen since his incarceration. In addition to several volumes of essays, letters, and unpublished books currently housed at the University of Michigan's Labadie Collection, Kaczynski has published two books. The first, Technological Slavery: The Collected Writings of Theodore J. Kaczynski, a.k.a. "The Unabomber" (2010), is both an anthology of previously unpublished essays related to his anti-technology philosophy, as well as an expanded elaboration on the ideas in Industrial Society and Its Future in the form of letters to various academics and other writers.[103] His most recent work, Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How (2016), is a comprehensive historical analysis of the effects of technology on society, arguing in detail why the control of technology and the prediction and management of society are impossible. Additionally, the book proposes a new framework for organizing and motivating people to make "meaningful and lasting change."[104]

Related works and influences

As a critique of technological society, the manifesto echoed contemporary critics of technology and industrialization, such as John Zerzan, Jacques Ellul (whose The Technological Society was referenced in a 1971 essay by Kaczynski),[105] Rachel Carson, Lewis Mumford and E. F. Schumacher.[106] Its idea of the "disruption of the power process" similarly echoed social critics emphasizing the lack of meaningful work as a primary cause of social problems, including Mumford, Paul Goodman, and Eric Hoffer.[106] The general theme was also addressed by Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, which Kaczynski references.[107] Kaczynski's ideas of "oversocialization" and "surrogate activities" recall Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents and his theories of rationalization and sublimation (the latter term being used three times in the manifesto to describe surrogate activities).[108]

In a Wired article on the dangers of technology, titled "Why The Future Doesn't Need Us" (2000), Bill Joy, cofounder of Sun Microsystems, quoted Ray Kurzweil's The Age of Spiritual Machines, which quoted a passage by Kaczynski on the types of society that might develop if human labor were entirely replaced by artificial intelligence. Joy wrote that Kaczynski is "clearly a Luddite" but "simply saying this does not dismiss his argument," and stated "I saw some merit in the reasoning in this single passage [and] felt compelled to confront it."[109]

Anders Behring Breivik, the perpetrator of the July 22, 2011 bombing and massacre in Norway,[110][111] published a manifesto in which large chunks of text were copied and pasted from Industrial Society and Its Future, with certain terms substituted (e.g., replacing "leftists" with "cultural Marxists" and "multiculturalists").[112][113]

Search

Before the publication of Industrial Society and Its Future, Ted Kaczynski's brother, David Kaczynski, was encouraged by his wife Linda to follow up on suspicions that Ted was the Unabomber.[114] David Kaczynski was at first dismissive, but progressively began to take the likelihood more seriously after reading the manifesto a week after it was published in September 1995. David Kaczynski browsed through old family papers and found letters dating back to the 1970s written by Ted and sent to newspapers protesting the abuses of technology and which contained phrasing similar to what was found in Industrial Society and Its Future.[115]

Before the manifesto was published, the FBI held many press conferences asking the public to help identify the Unabomber. They were convinced that the bomber was from the Chicago area (where he began his bombings), had worked or had some connection in Salt Lake City, and by the 1990s was associated with the San Francisco Bay Area. This geographical information, as well as the wording in excerpts from the manifesto that were released before the entire manifesto was published, persuaded David Kaczynski's wife, Linda, to urge her husband to read the manifesto.[116]

After the manifesto was published, the FBI received over a thousand calls a day for months in response to the offer of a $1 million reward for information leading to the identity of the Unabomber. Many letters claiming to be from the Unabomber were also sent to the UNABOM Task Force, and thousands of suspect leads were reviewed. While the FBI was occupied with new leads, David Kaczynski hired private investigator Susan Swanson in Chicago to investigate Ted's activities discreetly. The Kaczynski brothers had become estranged in 1990, and David had not seen Ted for ten years. David later hired Washington, D.C. attorney Tony Bisceglie to organize evidence acquired by Swanson, and make contact with the FBI, given the likely difficulty in attracting the FBI's attention. He wanted to protect his brother from the danger of an FBI raid, such as the Ruby Ridge or the Waco Siege, since he assumed Ted would not take kindly to being contacted by the FBI and would be likely to react violently.[117]

In early 1996, former FBI hostage negotiator and criminal profiler Clinton R. Van Zandt was contacted by an investigator working with Tony Bisceglie. Bisceglie asked Van Zandt to compare the manifesto to typewritten copies of handwritten letters David had received from his brother. Van Zandt's initial analysis determined that there was better than a 60 percent chance that the same person had written the letters as well as the manifesto, which had been in public circulation for half a year. Van Zandt's second analytical team determined an even higher likelihood that the letters and the manifesto were the product of the same author. He recommended that Bisceglie's client immediately contact the FBI.[117]

In February 1996, Bisceglie provided a copy of the 1971 essay written by Ted Kaczynski to the FBI. At the UNABOM Task Force headquarters in San Francisco, Supervisory Special Agent Joel Moss immediately recognized similarities in the writings. Linguistic analysis determined that the author of the essay papers and the manifesto were almost certainly the same. When combined with facts gleaned from the bombings and Kaczynski's life, that analysis provided the basis for a search warrant.

David Kaczynski had tried to remain anonymous at first, but he was soon identified, and within a few days an FBI agent team was dispatched to interview David and his wife with their attorney in Washington, D.C. At this and subsequent meetings, David provided letters written by his brother in their original envelopes, allowing the FBI task force to use the postmark dates to add more detail to their timeline of Ted's activities. David developed a respectful relationship with the primary Task Force behavioral analyst, Special Agent Kathleen M. Puckett, whom he met many times in Washington, D.C., Texas, Chicago, and Schenectady, New York, over the nearly two months before the federal search warrant was served on Kaczynski's cabin.[118]

David Kaczynski had once admired and emulated his older brother, but had later decided to leave the survivalist lifestyle behind.[119] He had received assurances from the FBI that he would remain anonymous and that his brother would not learn who had turned him in, but his identity was leaked to CBS News in early April 1996. CBS anchorman Dan Rather called FBI director Louis Freeh, who requested 24 hours before CBS broke the story on the evening news. The FBI scrambled to finish the search warrant and have it issued by a federal judge in Montana; afterwards, an internal leak investigation was conducted by the FBI, but the source of the leak was never identified.[119] In 1996 the Evergreen Park Community High School was also placed on lockdown while FBI agents searched Kaczynski's school records. At the end of that school day, students were greeted by reporters asking how they felt about going to the same high school the Unabomber had attended. That night the news story was released to public.

Paragraphs 204 and 205 of the FBI search and arrest warrant for Ted Kaczynski stated that "experts"—many of them academics consulted by the FBI—believed the manifesto had been written by "another individual, not Theodore Kaczynski".[72] As stated in the affidavit, only a handful of people believed Kaczynski was the Unabomber before the search warrant revealed the cornucopia of evidence in Kaczynski's isolated cabin. The search warrant affidavit written by FBI Inspector Terry D. Turchie reflects this conflict, and is striking evidence of the opposition to Turchie and his small cadre of FBI agents that included Moss and Puckett—who were convinced Kaczynski was the Unabomber—from the rest of the UNABOM Task Force and the FBI in general:

204. Your affiant is aware that other individuals have conducted analyses of the UNABOM Manuscript __ determined that the Manuscript was written by another individual, not Kaczynski, who had also been a suspect in the investigation. 205. Numerous other opinions from experts have been provided as to the identity of the unabomb subject. None of those opinions named Theodore Kaczynski as a possible author.[72]

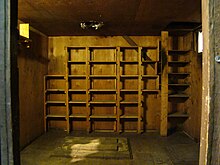

Arrest

FBI agents arrested Kaczynski on April 3, 1996, at his cabin, where he was found in an unkempt state. A search of his cabin revealed a cache of bomb components, 40,000 hand-written journal pages that included bomb-making experiments, descriptions of the Unabomber crimes and one live bomb, ready for mailing. They also found what appeared to be the original typed manuscript of Industrial Society and Its Future.[120] By this point, the Unabomber had been the target of the most expensive investigation in FBI history.[121]

After his capture, theories emerged that postulated Kaczynski as being the Zodiac Killer. Among the links that raised suspicion was the fact that Kaczynski lived in the San Francisco Bay Area from 1967 to 1969 (the same period that most of the Zodiac's confirmed killings occurred in California), that both individuals were highly intelligent with an interest in bombs and codes, and that both wrote letters to newspapers demanding the publication of their works with the threat of continued violence if the demand was not met. However, Kaczynski's whereabouts could not be verified for all of the killings, and the gun and knife murders committed by the Zodiac Killer differ from Kaczynski's bombings, so he was not further pursued as a suspect. Robert Graysmith, author of the 1986 book Zodiac, said the similarities are "fascinating" but purely coincidental.[122]

The early hunt for the Unabomber portrayed a perpetrator far different from the eventual suspect. Industrial Society and Its Future consistently uses "we" and "our" throughout, and at one point in 1993 investigators sought an individual whose first name was "Nathan" due to a fragment of a note found in one of the bombs,[73] but when the case was presented to the public, authorities denied that there was ever anyone other than Kaczynski involved in the crimes.[114]

Trial

Kaczynski's lawyers, headed by Montana federal defender Michael Donahoe and Judy Clarke, attempted to enter an insanity defense to avoid the death penalty, but Kaczynski rejected this plea. A court-appointed psychiatrist diagnosed Kaczynski as suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, but declared him competent to stand trial.[123] In his 2010 book Technological Slavery, Kaczynski recalls that two prison psychologists, James Watterson and Michael Morrison, who visited him almost every day for a period of four years told him that they saw no indication that he suffered from any such serious mental illness, and that the paranoid schizophrenia diagnosis was "ridiculous" and a "political diagnosis." Morrison also made remarks to him about psychologists and psychiatrists providing any desired diagnosis if they are well paid for doing so.[124]

A federal grand jury indicted Kaczynski in April 1996 on 10 counts of illegally transporting, mailing, and using bombs. He was also charged with three counts of murder for the killings of Scrutton, Mosser, and Murray.[125] Initially, the government prosecution team indicated that it would seek the death penalty for Kaczynski after it was authorized by United States Attorney General Janet Reno. David Kaczynski's attorney asked the former FBI agent who made the match between the Unabomber's manifesto and Kaczynski to ask for leniency—he was horrified to think that turning his brother in might result in his brother's death. Eventually, Kaczynski avoided the death penalty by pleading guilty to all the government's charges, on January 22, 1998. Later, Kaczynski attempted to withdraw his guilty plea, arguing it was involuntary. Judge Garland Ellis Burrell Jr. denied his request. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld that decision.[126]

On August 10, 2006, Burrell ordered that personal items seized in 1996 from Kaczynski's cabin should be sold at a "reasonably advertised Internet auction." Items the government considers to be bomb-making materials, such as writings that contain diagrams and "recipes" for bombs, were excluded from the sale. The auctioneer kept 10% of the sale price, while the rest of the proceeds went towards the $15 million in restitution that Burrell ordered Kaczynski to pay his victims.[127] Included among Kaczynski's holdings which were auctioned were his original writings, journals, correspondences, and other documents found in his cabin.[128][129][130] The judge ordered that all references in those documents that allude to any of his victims must be removed before they were sold. Kaczynski unsuccessfully challenged those ordered redactions in court on First Amendment grounds, arguing that any alteration of his writings is an unconstitutional violation of his freedom of speech.[131][132][133] The auction concluded in June 2011, and raised over $232,000.[134]

Imprisonment

Kaczynski is serving eight life sentences without the possibility of parole as Federal Bureau of Prisons register number 04475–046 at ADX Florence, a supermax prison in Florence, Colorado.[131][135] When asked if he was afraid of losing his mind in prison, Kaczynski replied:

No, what worries me is that I might in a sense adapt to this environment and come to be comfortable here and not resent it anymore. And I am afraid that as the years go by that I may forget, I may begin to lose my memories of the mountains and the woods and that's what really worries me, that I might lose those memories, and lose that sense of contact with wild nature in general. But I am not afraid they are going to break my spirit.[10]

Kaczynski has been an active writer in prison. The Labadie Collection, part of the University of Michigan's Special Collections Library, houses Kaczynski's correspondence from over 400 people since his arrest in April 1996, including carbon copy replies, legal documents, publications, and clippings.[136][137] The names of most correspondents will be kept sealed until 2049.[136][138]

Kaczynski's cabin was removed and was to be destroyed. Kaczynski said he gave it to Scharlette Holdman, an investigator on Kaczynski's defense team.[139] It was seized by the U.S. government and is on display at the Newseum in Washington, D.C.[140] In a three-page handwritten letter to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Kaczynski objected to the public exhibition of the cabin, claiming it was being exhibited despite victims' objections to the generation of publicity connected with the UNABOM case.[141]

In a letter dated October 7, 2005, Kaczynski offered to donate two rare books to the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies at Northwestern University's campus in Evanston, Illinois, the location of the first two attacks. The recipient, David Easterbrook, turned the letter over to the university's archives. Northwestern rejected the offer, noting that the library already owned the volumes in English and did not desire duplicates.[142]

On May 24, 2012, Kaczynski submitted his current information to the Harvard University alumni association. He listed his eight life sentences as "awards" and his current occupation as "prisoner."[143]

See also

- Italian Unabomber, a suspected militant responsible for a similar outbreak of bomb distribution in Italy

- Unabomber for President, a political campaign which aimed to elect the Unabomber in the 1996 United States presidential election

- In the media

- Das Netz, a film about Kaczynski

- Manhunt: Unabomber, a television series about Kaczynski

- P.O. Box Unabomber, a theatre play about Kaczynski

- Unabomber: The True Story, a television film about Kaczynski

References

- ^ "Inmate Locator". Bop.gov. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Solomon (Special Agent in Charge, Miami Division), Jonathan (February 6, 2008). "Major Executive Speeches". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gautney, Heather (2010). Protest and Organization in the Alternative Globalization Era: NGOs, Social Movements, and Political Parties. ISBN 978-023-0620-24-7. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

... claimed to be from 'the anarchist group calling ourselves FC

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hassell, Maria R; von Hassell, Agostino (July 9, 2009). A New Understanding of Terrorism: Case Studies, Trajectories and Lessons Learned. ISBN 978-144-1901-15-6. Archived from the original on January 24, 2016.

... Kaczynski was a disenchanted mathematics professor turned anarchist

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sue Mahan; Pamala L. Griset (2007). Terrorism in Perspective. Sage Publications. ISBN 978-141-2950-15-2. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chase, Alston (2003). Harvard and the Unabomber (1 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-039-3020-02-1.

- ^ Chase, Alston (2003). Harvard and the Unabomber: The Education of an American Terrorist. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0393020029.

- ^ Alston Chase (June 1, 2000). "Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber". The Atlantic Monthly. pp. 41–65. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Haas, Michaela. "My Brother, the Unabomber". Life Tips. Medium. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g "Interview with Ted Kaczynski, Administrative Maximum Facility Prison, Florence, Colorado, USA". Earth First Journal!. June 1999. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Howlett, Debbie (November 13, 1996). "FBI Profile: Suspect is educated and isolated". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

The 17-year search for the bomber has been the longest and costliest investigation in FBI history.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Claiborne, William (August 21, 1998). "FBI Gives Reward to Unabomber's Brother". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Glaberson, William (February 9, 1998). "Kaczynski Can't Drop Lawyers Or Block a Mental Illness Defense". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - ^ Times Staff Writers (April 14, 1996). "Adrift in Solitude, Kaczynski Traveled a Lonely Journey". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j McFadden, Robert D. (May 26, 1996). "Prisoner of Rage – A special report.; From a Child of Promise to the Unabom Suspect". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ted Kaczynski: Evil man, or tortured soul?". CNN. November 28, 2009. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kovaleski, Serge F.; Adams, Lorraine (June 16, 1996). "A STRANGER IN THE FAMILY PICTURE". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Kaczynski brothers and neighbors". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Alston, Chase (2004) [2003]. A Mind for Murder – The Education of The Unabomber and the Origins of Modern Terrorism (1 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc. pp. 107–108. ISBN 0-393-32556-3. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff writer(s) (November 13, 1996). "Kaczynski: Too smart, too shy to fit in". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ferguson, Paul (1997). "A loner from youth". CNN. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Karr-Morse, Robin (January 3, 2012). Scared Sick: The Role of Childhood Trauma in Adult Disease (2 ed.). Basic Books. ISBN 978-046-5013-54-8. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Achenbach, Joel; Kovaleski, Serge F. (April 7, 1996). "THE PROFILE OF A LONER". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Martin, Andrew; Becker, Robert (April 16, 1996). "Egghead Kaczynski Was Loner In High School". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hickey, Eric W. (2003). Encyclopedia of Murder and Violent Crime. SAGE Publications. p. 268.

- ^ Song, David (May 21, 2012). "Theodore J. Kaczynski". The Harvard Crimson. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Alston, Chase (June 2000). "Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 285, no. 6. pp. 41–63. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ RadioLab (June 28, 2010). "Oops". Archived from the original on September 8, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cockburn, Alexander (October 18, 1999). "CIA Shrinks & LSD". CounterPunch. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Stampfl, Karl (March 16, 2006). "He came Ted Kaczynski, he left The Unabomber". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Ostrom, Carol M. (April 6, 1996). "Unabomber Suspect Is Charged – Montana Townsfolk Showed Tolerance For 'The Hermit'". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bullough, John. "Published [Academic] Works of Theodore Kaczynski". Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Howe, Peter J.; Dembner, Alice (April 5, 1996). "Meteoric Talent that Burned Out". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Li, Ivy (November 10, 2016). "A neo-Luddite manifesto?". The Tech. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Crenson, Matt (July 21, 1996). "Kaczynski's Dissertation Would Leave Your Head Spinning". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Perez-Pena, Richard (April 5, 1996). "On the Suspect's Trail: the Suspect; Memories of His Brilliance, And Shyness, but Little Else". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Graysmith, Robert (1998). Unabomber: A Desire to Kill. Berkeley Publishing Group. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0425167259.

- ^ Morris, Willy (April 6, 1996). "Kaczynski Ended Career in Math with no Explanation". Buffalo News.

- ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (June–July 1964). "Another Proof of Wedderburn's Theorem". American Mathematical Monthly. 71 (6): 652–653.

- ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (June–July 1964). "Advanced Problem 5210". American Mathematical Monthly. 71 (6): 689.

- ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (June–July 1965). "Distributivity and (-1)x = -x (Advanced Problem 5210, with Solution by Bilyeu, R.G.)". American Mathematical Monthly. 72 (6): 677–678.

- ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (1965). "Boundary Functions for Functions Defined in a Disk". Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics, 14, 589-612. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (November 1966). "On a Boundary Property of Continuous Functions". Michigan Mathematical Journal, 13, 313-320. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (1967). "Boundary Functions (fragment)". Doctoral dissertation. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (March–April 1968). "Note on a Problem of Alan Sutcliffe". Mathematics Magazine, 41(2), 84-86. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (March 1969). "Boundary Functions for Bounded Harmonic Functions" (PDF). Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 137, 203-209. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (July 1969). "Boundary Functions and Sets of Curvilinear Convergence for Continuous Functions" (PDF). Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 141, 107-125. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (November 1969). "The Set of Curvilinear Convergence of a Continuous Function Defined in the Interior of a Cube" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 23, 323-327. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (January–February 1971). "Problem 787". Mathematics Magazine. 44 (1): 41.

- ^ Kaczynski, T.J. (November–December 1971). "A Match Stick Problem (Problem 787, with Solutions by Gibbs, R.A. and Breisch, R.L.)". Mathematics Magazine. 44 (5): 294–296.

- ^ Bagemihl, F.; Piranian, G. (1961). "Boundary Functions for Functions Defined in a Disk". Michigan Mathematical Journal, 8(2), 201-207. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McMillan, J.E. (1966). "Boundary Properties of Functions Continuous in a Disc". Michigan Mathematical Journal, 13, 299-312. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Snyder, L.E. (1967). "Bi-Arc Boundary Functions" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 18, 808-811. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pudwell, Lara (2007). "Digit Reversal Without Apology" (PDF). Mathematics Magazine, 80 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 31, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "125 Montana Newsmakers: Ted Kaczynski". Great Falls Tribune. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kifner, John (April 5, 1996). "ON THE SUSPECT'S TRAIL: LIFE IN MONTANA; Gardening, Bicycling And Reading Exotically". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "The Unabomber: A Chronology (1978–1982)". Court TV. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnston, David (April 16, 1996). "Cabin's Inventory Provides Insight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ted Kaczynski's Family on 60 Minutes". CBS News. September 15, 1996. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gortelmann, Josh (November 13, 1996). "Kaczynski was fired '78 after allegedly harassing co-worker". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Johnson, Dirk (April 19, 1996). "Woman Denies Romance With Unabomber Suspect". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Graysmith, Robert (1997). Unabomber: A Desire to Kill. Berkley Publishing Group. p. 74. ISBN 0425167259.

- ^ Franks, Lucinda (July 22, 1996). "Don't Shoot". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Labaton, Stephen (October 7, 1993). "Clue and $1 million Reward in Case of the Serial Bomber". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Unabomber: A Chronology (1985–1987)". Court TV. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Claiborne, William (April 11, 1996). "Kaczynski Beard May Confuse Witness". The Washington Post. p. A11.

- ^ Lavandera, Ed (June 6, 2008). "Unabomber's brother, victim forge unique friendship". CNN. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Shogren, Elizabeth (June 25, 1993). "Mail Bomb Attack Leaves Yale Computer Scientist in Critical Condition". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "The Unabomber: A Chronology (1988–1995)". Court TV. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "U.S. v. Kaczynski Trial Transcripts". Court TV. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Freedom Club. "The Communiques of Freedom Club, § Letter to San Francisco Examiner". Wildism.org. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Affidavit of Assistant Special Agent in Charge". Court TV. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Death in the Mail – ; Kleinfield, N. R". The New York Times. December 18, 1994. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The end of anon: literary sleuthing from Shakespeare to Unabomber". The Guardian. London. August 16, 2001. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Graysmith, Robert Unabomber: A Desire to Kill (1997) Berkely Publishing ISBN 0-425-16725-9

- ^ "The Unabomber's Targets: An Interactive Map". CNN. 1997. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Lardner, George; Adams, Lorraine (April 14, 1996). "To Unabomb Victims, a Deeper Mystery". The Washington Post. p. A01. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chase, Alston. A Mind for Murder: The Education of the Unabomber and the Origins of Modern Terrorism. W. W. Norton & Company, Incorporated. p. 84. ISBN 0-393-02002-9. Google Book Search. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ "Unabomber Sends New Warnings". latimes. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff writer(s) (April 21, 1996). "A DELICATE DANCE". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Excerpts From Letter by 'Terrorist Group,' FC, Which Says It Sent Bombs". The New York Times. April 26, 1995. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Elson, John (July 10, 1995). "Murderer's Manifesto". Time. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "WashingtonPost.com: Unabomber Special Report". Archived from the original on May 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "WashingtonPost.com:". Archived from the original on May 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chase, Alston. A Mind for Murder: The Education of the Unabomber and the Origins of Modern Terrorism. W. W. Norton & Company, Incorporated. p. 85. ISBN 0-393-02002-9. Google Book Search. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Crain, Craig (1998). "The Bard's fingerprints". Lingua Franca: 29–39.

- ^ a b Staff writer(s) (September 19, 1995). "Excerpts from Unabomber document". United Press International.

- ^ Kaczynski 1995, p. 1 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKaczynski1995 (help)

- ^ a b c d e Adams, Brooke (April 11, 1996). "FROM HIS TINY CABIN TO THE LACK OF ELECTRICTY AND WATER, KACZYNSKI'S SIMPLE LIFESTYLE IN MONTANA MOUNTAINS COINCIDED WELL WITH HIS ANTI-TECHNOLOGY VIEWS". Deseret News.

- ^ Katz, Jon (April 17, 1998). "THE UNABOMBER'S LEGACY, PART I". Wired.

- ^ a b Sale, Kirkpatrick (September 25, 1995). "Is There Method In His Madness?". The Nation. p. 306.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (September 25, 1995). "Is There Method In His Madness?". The Nation. p. 308.

- ^ a b c Didion, Joan (April 23, 1998). "Varieties of Madness". The New York Review of Books.

- ^ a b Chase, Alston (2000). "Harvard and the Making of the Unabomber". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Finnegan, William. "The Unabomber Returns". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012.