John Harvard (clergyman): Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES -->Colledge<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES --> |

<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES -->Colledge<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES --> |

||

agreed upon formerly to |

agreed upon formerly to |

||

<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES --> |

<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES -->bee<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES --> |

||

built at |

built at |

||

<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES -->Cambridg shalbee<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES --> |

<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES -->Cambridg shalbee<!-- DO NOT "FIX" DIRECT QUOTES --> |

||

Revision as of 18:36, 3 October 2014

John Harvard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 November 1607 Southwark, England |

| Died | 14 September 1638 (aged 30) |

| Cause of death | Tuberculosis |

| Alma mater | Emmanuel College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Pastor |

| Known for | Benefactor and namesake of Harvard College |

| Children | None |

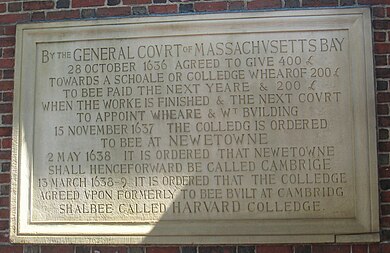

John Harvard (26 November 1607 – 14 September 1638) was an English minister in America, "a godly gentleman and a lover of learning",[1] whose deathbed[2] bequest to the "schoale or Colledge" recently undertaken by the Massachusetts Bay Colony was so gratefully received that it was consequently ordered "that the Colledge agreed upon formerly to bee built at Cambridg shalbee called Harvard Colledge." [3]

Life

Early life

Harvard was born and raised in Southwark, England, the fourth of nine children of Robert Harvard (1562–1625), a butcher and tavern owner, and his wife Katherine Rogers (1584–1635), a native of Stratford-upon-Avon whose father, Thomas Rogers (1540–1611), was an associate of Shakespeare's father, both serving on the borough corporation's council. He was baptised in the parish church of St Saviour's (now Southwark Cathedral)[4] and attended St Saviour's Grammar School, where his father was a member of the governing body as being also a Warden of the Parish Church.

In 1625, the plague reduced the immediate family to only John, his brother Thomas, and their mother. Katherine was soon remarried—firstly in 1626 to John Elletson (1580–1626), who died within a few months, then (1627) to Richard Yearwood (1580–1632). She died in 1635, Thomas in 1637.

Education and ordination

Left with some property, Harvard's mother was able to send him to Emmanuel College, Cambridge,[5] where he earned his B.A. in 1632[6] and M.A. in 1635,[7] and was subsequently ordained a dissenting minister.[5]

Marriage and career

In 1636, he married Ann Sadler (1614–55) of Ringmer, sister of his college classmate John Sadler.

In the spring or summer of 1637, the couple emigrated to New England, where Harvard became a freeman of Massachusetts and,[5] settling in Charlestown, a teaching elder of the First Church there[8] and an assistant preacher.[7] In 1638, a tract of land was deeded[clarification needed] to him there, and he was appointed that same year to a committee "to consider of some things tending toward a body of laws."[5] [clarification needed]

Death

On 14 September 1638, he died of tuberculosis and was buried at Charlestown's Phipps Street Burying Ground. In 1828, Harvard University alumni erected a granite monument to his memory there,[5][9] his original stone having disappeared during the American Revolution.[8]

Benefactor of Harvard College

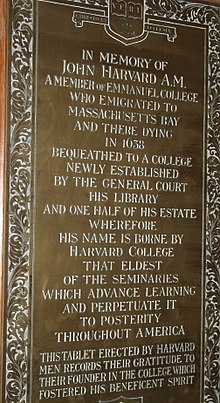

Two years before Harvard's death the Massachusetts Bay Colony—desiring to "advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity: dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches, when our present ministers shall lie in the dust"—appropriated £400 toward a "schoale or colledge"[3] at what was then called Newtowne.[10] In an oral will spoken to his wife[11] the childless Harvard, who had inherited considerable sums from his father, mother, and brother,[12] bequeathed to the school £780 (half of his monetary estate, with the remainder to his wife)[4] as well as—and perhaps more importantly[13]—his 320-volume scholar's library.[5] It was subsequently ordered "that the Colledge agreed upon formerly to bee built at Cambridg shalbee called Harvard Colledge."[3] (Even before Harvard's death, Newtowne had been renamed[3] Cambridge, after the English university attended by many early colonists, including Harvard himself.)[14]

A statue in Harvard's honor—not, however, a likeness of him, there being nothing to indicate what he had looked like[7]—is a prominent feature of Harvard Yard (see John Harvard statue) and was featured on a 1986 stamp, part of the United States Postal Service's Great Americans series.[15] A figure representing him also appears in a stained-glass window in the chapel of Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge.[7]

The John Harvard Library in Southwark, London, is named in Harvard's honor, as is the Harvard Bridge that connects Boston to Cambridge.[16]

References

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison, The founding of Harvard College (1936) Appendix D, and pp 304-5

- ^ Conrad Edick Wright, John Harvard: Brief life of a Puritan philanthropist Harvard Magazine. January–February, 2000. "By the time the Harvards settled in Charlestown John must already have been in failing health ... Consumption kills slowly. By the time Harvard died, he knew what he wanted to do with his estate."

- ^ a b c d The Charter of the President and Fellows of Harvard College[dead link]

- ^ a b Rowston, Guy (2006). Southwark Cathedral – The authorised Guide.

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1892). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ "Harvard, John (HRVT627J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ a b c d Emmanuel College: John Harvard Retrieved 2012-05-01

- ^ a b Melnick, Arseny James. "Celebrating the Life and Times of JOHN HARVARD". Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Edward Everett (1850). Orations and speeches on various occasions. Vol. I. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown. pp. 185–189.

- ^ New England's First Fruits (1643). http://books.google.com/books?id=gXkFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA16

- ^ Callan, Richard L. 100 Dears of Solitude: John Harvard Finishes His First Century. The Harvard Crimson. April 28, 1984. Retrieved October 13, 2012

- ^

. Vol. 16. Harvard Graduates' Magazine Association. 1908 http://books.google.com/books?id=BDFYAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR5. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Alfred C. Potter, "The College Library." Harvard Illustrated Magazine, vol. IV no. 6, March 1903, pp. 105–112.

- ^ Degler, Carl Neumann (1984). Out of Our Pasts: The Forces That Shaped Modern America. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-131985-3. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ usstampgallery.com: John Harvard

- ^ Alger, Alpheus B.; Matthews, Nathan Jr. (1892). Harvard Bridge: Boston to Cambridge, March 1892. Boston, Massachusetts: Rockwell and Churchill. p. 14. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

Further reading

- Shelley, Henry C. (1907). John Harvard and His Times. Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown, and Co.

- Rendle, William (1885). John Harvard, St. Saviour's, Southwark, and Harvard University, U.S.A. London: J.C. Francis.

External links

- Harvard House The home of Katherine Rogers in Stratford-Upon-Avon