Charles Darwin: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

rvv from bobby's v |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{dablink|For other uses see [[Darwin (disambiguation)]]}} |

{{dablink|For other uses see [[Darwin (disambiguation)]]}} |

||

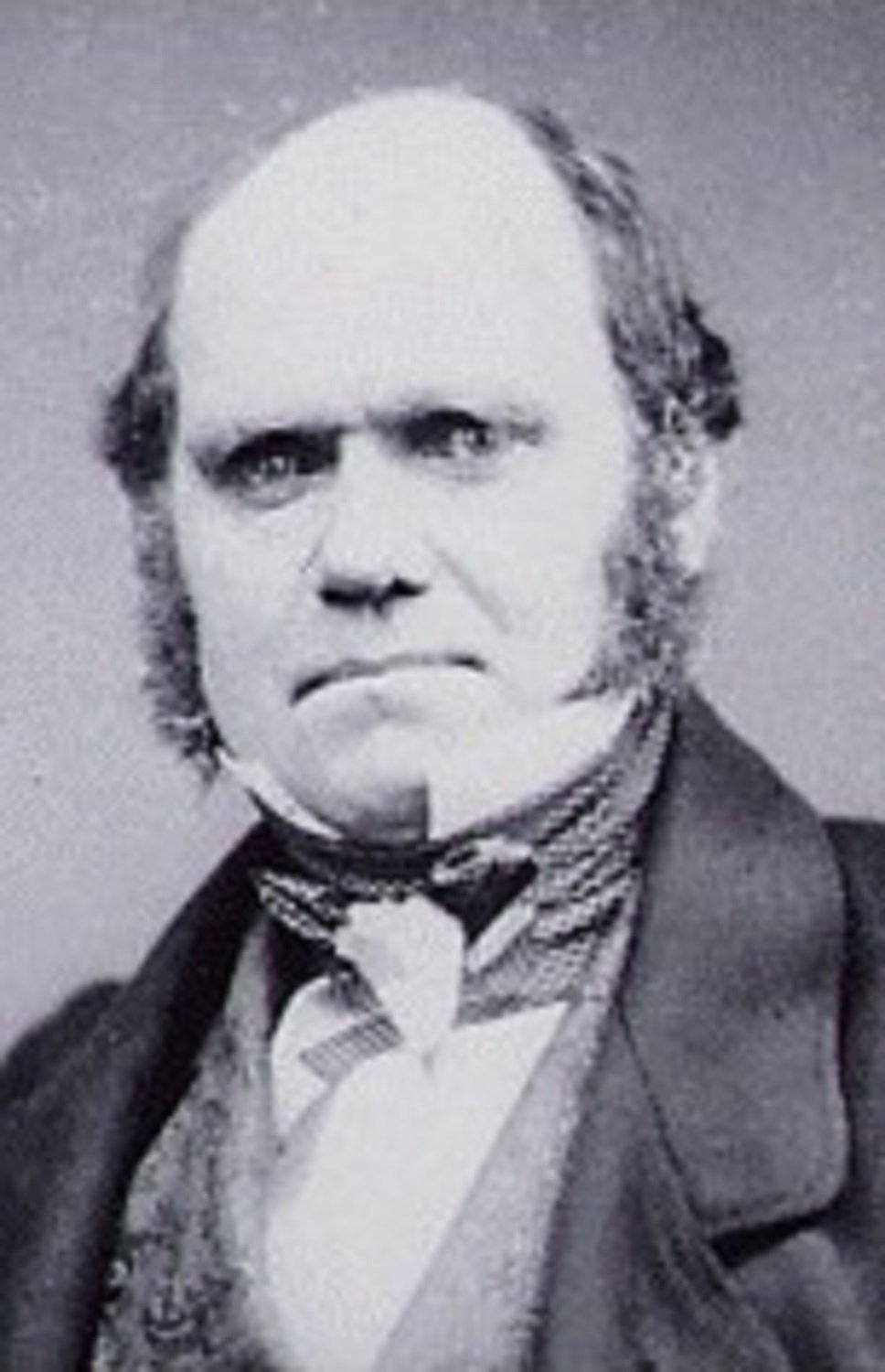

[[Image:Charles_Darwin_1881.jpg|thumb|right|200px|In his lifetime Charles Darwin gained international fame as a controversial and influential scientist.]] |

[[Image:Charles_Darwin_1881.jpg|thumb|right|200px|In his lifetime Charles Darwin gained international fame as a controversial and influential scientist.]] |

||

'''Charles |

'''Charles Robert Darwin''' ([[February 12]], [[1809]]–[[April 19]], [[1882]]) was a [[United Kingdom|British]] [[natural history|naturalist]] who achieved lasting fame as the originator of the [[theory]] of [[evolution]] through [[natural selection]]. |

||

He developed his interest |

He developed his interest in natural history while studying first medicine, then [[theology]], at university. Darwin's [[The Voyage of the Beagle|five-year voyage]] on the [[HMS Beagle|''Beagle'']] brought him eminence as a [[geology|geologist]] and fame as a popular author. His [[biology|biological]] observations led him to study the [[transmutation of species]] and develop his theory of natural selection in 1838. Fully aware of the likely reaction, he confided only in close friends and continued his research to meet anticipated objections, but in 1858 the information that [[Alfred Russel Wallace]] now had a similar theory forced early joint [[publication of Darwin's theory]]. |

||

His |

His 1859 book ''The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'' (usually abbreviated to ''[[The Origin of Species]]'') established evolution by [[common descent]] as the dominant scientific theory of diversification in nature. He was made a [[Fellow of the Royal Society]], continued his research, and wrote a series of books on plants and animals, including humankind, notably ''[[The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex]]'' and ''[[The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals]]''. His last book was about [[earthworm]]s. |

||

In recognition of Darwin's pre-eminence |

In recognition of Darwin's pre-eminence, he was buried in [[Westminster Abbey]], close to [[William Herschel]] and [[Isaac Newton]]. |

||

== Life == |

== Life == |

||

=== Early |

=== Early life === |

||

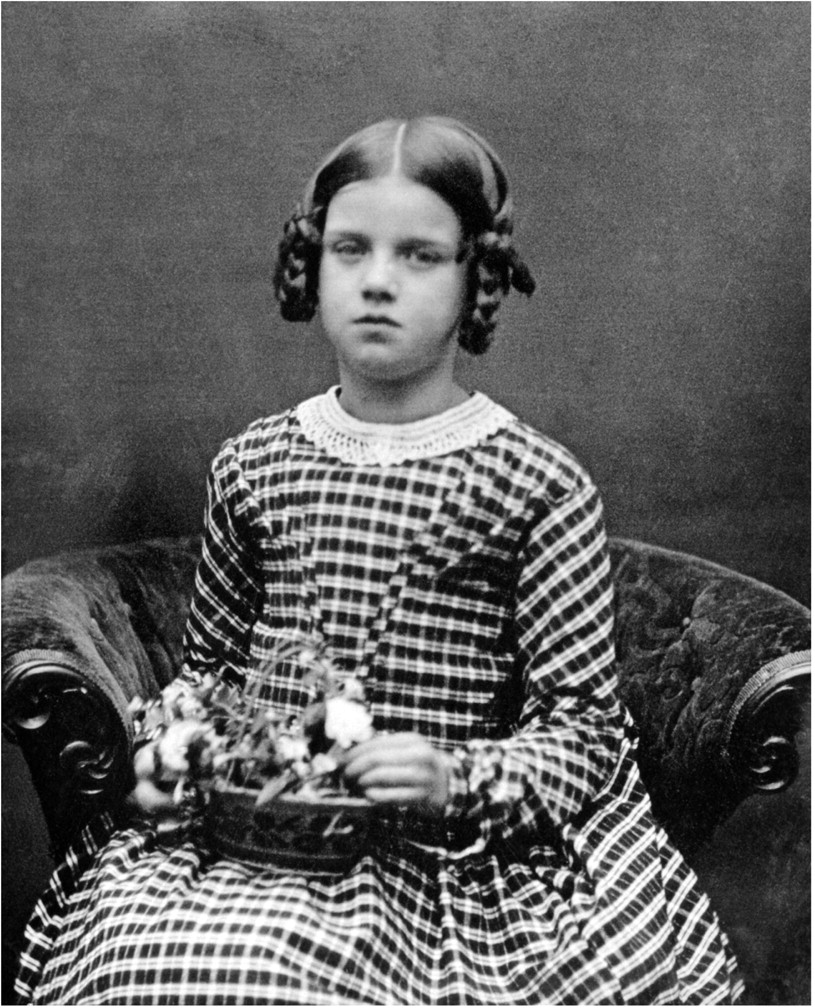

[[Image:Charles Darwin 1816.jpg|thumb|190px|The seven-year-old Charles Darwin in 1816, a year before the sudden loss of his mother.]] |

[[Image:Charles Darwin 1816.jpg|thumb|190px|The seven-year-old Charles Darwin in 1816, a year before the sudden loss of his mother.]] |

||

{{main|Charles Darwin's education}} |

{{main|Charles Darwin's education}} |

||

| Line 249: | Line 249: | ||

[[gd:Charles Darwin]] |

[[gd:Charles Darwin]] |

||

[[gl:Charles Darwin]] |

[[gl:Charles Darwin]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[hi:चार्ल्स डार्विन]] |

[[hi:चार्ल्स डार्विन]] |

||

[[hr:Charles Darwin]] |

[[hr:Charles Darwin]] |

||

[[id:Charles Darwin]] |

[[id:Charles Darwin]] |

||

[[io:Charles Darwin]] |

|||

[[is:Charles Darwin]] |

[[is:Charles Darwin]] |

||

[[it:Charles Darwin]] |

[[it:Charles Darwin]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[ku:Charles Darwin]] |

[[ku:Charles Darwin]] |

||

[[la:Carolus Darwin]] |

[[la:Carolus Darwin]] |

||

Revision as of 14:42, 9 November 2005

Charles Robert Darwin (February 12, 1809–April 19, 1882) was a British naturalist who achieved lasting fame as the originator of the theory of evolution through natural selection.

He developed his interest in natural history while studying first medicine, then theology, at university. Darwin's five-year voyage on the Beagle brought him eminence as a geologist and fame as a popular author. His biological observations led him to study the transmutation of species and develop his theory of natural selection in 1838. Fully aware of the likely reaction, he confided only in close friends and continued his research to meet anticipated objections, but in 1858 the information that Alfred Russel Wallace now had a similar theory forced early joint publication of Darwin's theory.

His 1859 book The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (usually abbreviated to The Origin of Species) established evolution by common descent as the dominant scientific theory of diversification in nature. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society, continued his research, and wrote a series of books on plants and animals, including humankind, notably The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. His last book was about earthworms.

In recognition of Darwin's pre-eminence, he was buried in Westminster Abbey, close to William Herschel and Isaac Newton.

Life

Early life

Charles Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, England, on February 12, 1809 at his family home, the Mount House. He was the fifth of six children of Robert and Susannah Darwin (née Wedgwood), and the grandson of Erasmus Darwin on his father's side, of Josiah Wedgwood on his mother's side, both from the Darwin–Wedgwood family, a prominent English family which supported the Unitarian church. His mother died when he was only eight. When he went to the nearby Shrewsbury School the next year, he lived there as a "boarder".

In 1825 Darwin went to Edinburgh University to study medicine, but his revulsion at the brutality of surgery led him to neglect his medical studies. He studied taxidermy with a freed black slave from South America, and found his tales of the South American rainforest absorbing. In Darwin's second year he became active in student societies for naturalists. He became an avid pupil of Robert Edmund Grant, who enthusiastically followed the theories of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Charles's grandfather Erasmus concerning evolution by acquired characteristics. Grant's pioneering investigations of the life cycle of marine animals on the shores of the Firth of Forth found evidence for homology, the radical theory that all animals have similar organs and differ only in complexity. Darwin took part in these investigations, and in March 1827 made a presentation to the Plinian society of his discovery that the black spores often found in oyster shells were the eggs of a skate leech. He also sat in on Robert Jameson's natural history course, learning about stratigraphic geology and assisting with work on the collections of the Museum of Edinburgh University, then one of the largest museums in Europe.

In 1827, his father, unhappy that his younger son had no interest in becoming a physician, enrolled him in a Bachelor of Arts course at Christ's College, University of Cambridge, which would qualify him to be a clergyman. This was a sensible career move at a time when Anglican parsons were provided with a comfortable income, and when most naturalists in England were clergymen who saw it as part of their duties to explore the wonders of God's creation. At Cambridge, Darwin preferred riding and shooting to studying. Along with his cousin William Darwin Fox, he became engrossed in the craze at the time for the competitive collecting of beetles, and Fox introduced him to the Reverend John Stevens Henslow, professor of botany, for expert advice on beetles. Darwin subsequently joined Henslow's natural history course, becoming his "favourite pupil" and coming to be known as "the man who walks with Henslow". When exams began to loom, Darwin focused more on his studies and received private tuition from Henslow, whose subjects were mathematics and theology. Darwin became particularly enthused by the writings of William Paley, including the argument of divine design in nature. In his finals in January 1831, he performed well in theology and, having scraped through in classics, mathematics and physics, came tenth out of a pass list of 178.

Residential requirements now kept Darwin at Cambridge until June. In keeping with Henslow's example and advice, he was in no rush to take holy orders. Inspired by Alexander von Humboldt's Personal Narrative, he planned to visit the Madeira Islands to study natural history in the tropics with some classmates after graduation. To prepare for this project, Darwin now joined the geology course of the Reverend Adam Sedgwick, then worked him in mapping strata in Wales during summer break. Darwin was surveying strata in Wales on his own when his plans to visit Madeira were dashed by a message that his intended companion had died, but on his return home he received another letter. Henslow had recommended Darwin for the unpaid position of gentleman's companion to Robert FitzRoy, the captain of HMS Beagle, on a two-year expedition to chart the coastline of South America which would give Darwin valuable opportunities to develop his career as a naturalist. His father objected to the voyage, regarding it as a waste of time, but was persuaded by Josiah Wedgwood II to agree to his son's participation. This voyage became a five-year expedition that would lead to dramatic changes in countless fields of science.

Journey on the Beagle

The Beagle survey took five years, two-thirds of which Darwin spent exploring on land. He studied a rich variety of geological features, fossils and living organisms, and met a wide range of people, both native and colonial. He methodically collected an enormous number of specimens, many of them new to science, which would establish his reputation as a naturalist and make him one of the precursors of the field of ecology, particularly the notion of biocoenosis. His detailed notes formed the basis for his later work and provided social, political and anthropological insights into the areas he visited. While there, Darwin read Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology, which explained geological features as the outcome of gradual processes over huge periods of time, and wrote home that he was seeing landforms "as though he had the eyes of Lyell": stepped plains of shingle and seashells in Patagonia appeared to be raised beaches; in Chile, he experienced an earthquake that raised the land; and even high in the Andes, he was able to collect seashells. He theorized that coral atolls form on sinking volcanic mountains, and a survey of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands supported his theory.

In South America he discovered fossils of gigantic extinct megatheria and glyptodons in strata which showed no signs of catastrophe or change in climate. At the time, he thought them similar to African species, but after the voyage Richard Owen showed that the remains were of animals related to living creatures in the same area. In Argentina two species of rhea had separate but overlapping territories. Darwin found different mockingbirds on the nearby Galápagos Islands, and on returning to Britain he was shown that Galápagos tortoises and finches were also in distinct species based on the individual islands they inhabited. The Australian marsupial rat-kangaroo and platypus were such strikingly different creatures as to cause him to remark that "An unbeliever ... might exclaim 'Surely two distinct Creators must have been [at] work'." In the first edition of The Voyage of the Beagle, he explained species distribution in light of Charles Lyell's ideas of "centres of creation"; however, in later editions of this Journal he foreshadowed his use of Galápagos Islands fauna as evidence for evolution: "one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends."

Three natives of Tierra del Fuego returning with them as missionaries had become civilized over the previous two years, yet their relatives appeared to him savages little above animals. Within a year, the missionaries had reverted to savagery, yet preferred this to returning to civilization. This experience and his detestation of the slavery he saw elsewhere convinced him that the widespread concept of inferior races was incorrect, and that humanity was not as far removed from animals as his clerical friends believed.

While on board the ship, Darwin suffered from seasickness, in October 1833 he caught a fever in Argentina, and in July 1834, while returning from the Andes down to Valparaíso, he fell ill and spent a month in bed. From 1837 onwards Darwin was repeatedly incapacitated with episodes of stomach pains, vomiting, severe boils, palpitations, trembling and other symptoms, which particularly affected him at times of stress, such as when attending meetings or dealing with controversy over his theory. The cause of Darwin's illness was unknown during his lifetime, and attempts at treatment had little success. Recent speculation has suggested that in South America he caught Chagas disease from insect bites, leading to the later problems. Other possible causes include psychobiological problems.

Career in science, inception of theory

While Darwin was still on the voyage, Henslow carefully fostered his former pupil's reputation by giving selected naturalists access to the fossil specimens and printed copies of Darwin's geological writings. When the Beagle returned on October 2, 1836, Darwin was a celebrity in scientific circles. He visited his home in Shrewsbury and his father organised investments so that Darwin could become a self-funded gentleman scientist. After visiting Cambridge and getting Henslow to agree to work on botanical descriptions of modern plants he had collected, Darwin went round the London institutions to find the best naturalists available to describe his other collections for timely publication. An eager Charles Lyell met Darwin on 29 October and introduced him to the up-and-coming anatomist Richard Owen. After working on Darwin's collection of fossil bones at his Royal College of Surgeons, Owen caused great surprise by revealing that some were from gigantic extinct rodents and sloths. This enhanced Darwin's reputation. With Lyell's enthusiastic backing Darwin read his first paper to the Geological Society of London on January 4, 1837, arguing that the South American landmass was slowly rising. On the same day Darwin presented his mammal and bird specimens to the Zoological Society. The Mammalia were taken on by George R. Waterhouse. Though the birds seemed almost an afterthought, the ornithologist John Gould revealed that what Darwin had taken to be wrens, blackbirds and slightly differing finches from the Galápagos were all finches, but each was a separate species. Others on the Beagle including FitzRoy had also collected these birds and had been more careful with their notes, enabling Darwin to find which island each species had come from.

In London Charles stayed with his brother Erasmus and met inspiring savants at dinner parties. His brother's lady friend Miss Harriet Martineau was a writer whose stories promoted Malthusian Whig Poor Law reforms. Scientific circles were buzzing with ideas of Transmutation of species controversially associated with radicalism. Darwin preferred the respectability of his friends the Cambridge Dons, even though his ideas were pushing beyond their belief that natural history must justify religion and social order.

On February 17, 1837, Lyell used his presidential address at the Geographical Society to present Owen's findings to date on Darwin's fossils, pointing out the inference that extinct species were related to current species in the same locality. At the same meeting Darwin was elected to the Council of the Society. He had already been invited by FitzRoy to contribute a Journal based on his field notes as the natural history section of the captain's account of the Beagle's voyage. He now plunged into writing a book on South American Geology. At the same time he speculated on transmutation in his Red Notebook which he had begun on the Beagle. Another project he started was getting the expert reports on his collection published as a multivolume Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, and Henslow used his contacts to arrange a Treasury grant of £1,000 to sponsor this. Darwin finished writing his Journal around 20 June when King William IV died and the Victorian era began. In mid-July he began his secret "B" notebook on transmutation, and developed the hypothesis that where every island in the Galápagos Archipelago had its own kind of tortoise, these had originated from a single tortoise species and had adapted to life on the different islands in different ways.

Under pressure with organising Zoology and correcting proofs of his Journal, Darwin's health suffered. On September 20, 1837 he suffered "palpitations of the heart" and left for a month of recuperation in the country. He visited Maer Hall where his invalid aunt was being cared for by her spinster daughter Emma Wedgwood, and entertained his relatives with tales of his travels. His uncle Jos pointed out an area of ground where cinders had disappeared under loam and suggested that this might have been the work of earthworms. This gave Darwin the inspiration for a talk which he gave to the Geological Society on 1 November, on the unusually mundane subject of worm casts. He had avoided taking on official posts which would take valuable time, but by March Whewell had recruited him as Secretary of the Geological Society. Illness prompted Darwin to take a break from the pressure of work and he went "geologising" in Scotland. In glorious weather he visited Glen Roy to see the phenomenon known as "roads" which he identified as raised beaches.

Fully recuperated, he returned home to Shrewsbury. Pondering his career and prospects he drew up a list with columns headed "Marry" and "Not Marry". Having come down in favour, he discussed it with his father then went to visit his cousin Emma on July 29, 1838. He did not get around to proposing, but against his father's advice he told her of his ideas on transmutation. While his thoughts and work continued in London over the autumn he suffered repeated bouts of illness. On 11 November he returned and proposed to Emma, once more telling her his ideas. She accepted, but later wrote beseeching him to read from the Gospel of St. John a section on love and following the Way which also states that "If a man abide not in me...they are burned". He sent a warm reply which eased her concern, but she would continue to worry that his lapses of faith could endanger her hope that they would meet in an afterlife.

Darwin considered Malthus's argument that human populations breed beyond their means and compete to survive. He related this to the findings about species relating to localities, his enquiries into animal breeding, and ideas of Natural "laws of harmony". Towards the end of November 1838 he compared breeders selecting traits to a Malthusian Nature selecting from variants thrown up by "chance" so that "every part of newly acquired structure is fully practised and perfected", and thought this "the most beautiful part of my theory" of how species originated. He went house-hunting and eventually found "Macaw Cottage" in Gower Street, London, then moved his "museum" in over Christmas. He was showing the stress, and Emma wrote urging him to get some rest, almost prophetically remarking "So don't be ill any more my dear Charley till I can be with you to nurse you". On January 24, 1839 he was honoured by being elected as Fellow of the Royal Society and presented his paper on the Roads of Glen Roy.

Marriage and children

On January 29, 1839, Darwin married his cousin Emma Wedgwood at Maer in an Anglican ceremony arranged to also suit the Unitarians. After first living in Gower Street, London, the couple moved on September 17, 1842 to Down House in Downe (which is now open to public visits, south of Orpington). The Darwins had ten children, three of whom died early. Many of these and their grandchildren would later achieve notability themselves (see Darwin–Wedgwood family)

- William Erasmus Darwin (December 27, 1839–1914)

- Anne Elizabeth Darwin (March 2, 1841–April 22, 1851)

- Mary Eleanor Darwin (September 23, 1842–October 16, 1842)

- Henrietta Emma "Etty" Darwin (September 25, 1843–1929)

- George Howard Darwin (July 9, 1845–December 7, 1912)

- Elizabeth "Bessy" Darwin (July 8, 1847–1926)

- Francis Darwin (August 16, 1848–September 19, 1925)

- Leonard Darwin (January 15, 1850–March 26, 1943)

- Horace Darwin (May 13, 1851–September 29, 1928)

- Charles Waring Darwin (December 6, 1856–June 28, 1858)

Several of their children suffered illness or weaknesses, and Charles Darwin's fear that this might be due to the closeness of his and Emma’s lineage was expressed in his writings on the ill effects of inbreeding and advantages of crossing.

Development of theory

Darwin was now an eminent geologist in the scientific élite of clerical naturalists, settled with a private income. He had a vast amount of work to do, writing up his findings and theories, and supervising the preparation of the multivolume Zoology, which would describe his collections. He was convinced by his theory of evolution, but for a long time had been aware that transmutation of species was associated with the crime of blasphemy as well as with Radical democratic agitators in Britain who were seeking to overthrow society; thus, publication risked ruining his reputation. He embarked on extensive experiments with plants and consultations with animal husbanders, including pigeon and pig breeders, trying to find soundly based answers to all the arguments he anticipated when he presented his theory in public.

When FitzRoy's account was published in May 1839, Darwin's Journal and Remarks was a great success. Later that year it was published on its own, becoming the bestseller nowadays known as The Voyage of the Beagle. In December 1839, as Emma's first pregnancy progressed, Darwin suffered more illness and accomplished little during the following year.

Darwin made attempts to explain his theory to close friends, but they were slow to show interest and thought that selection must need a divine selector. In 1842 the family moved to Down House to escape the pressures of London. Darwin formulated a short "Pencil Sketch" of his theory, and by 1844 had written a 240-page "Essay" that expanded his early ideas on natural selection. Darwin completed his third Geological book in 1846; assisted by his friend, the young botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, he embarked on a huge study of barnacles. In 1847, Hooker read the "Essay" and sent notes that provided Darwin with the calm critical feedback that he needed.

To try to deal with his illness, Darwin went to a spa in Malvern in 1849, and to his surprise found that the two months of water treatment helped. In his work on barnacles he found "homologies" that supported his theory by showing that slightly changed body parts could serve different functions to meet new conditions. Then his treasured daughter Annie fell ill, reawakening his fears that his illness might be hereditary. After a long series of crises, she died and Darwin lost all faith in a beneficent God. He met the young naturalist Thomas Huxley who was to become a close friend and ally, then completed his work on barnacles (Cirripedia) in 1854 and turned his attention to his theory of species.

Announcement and publication of theory

In the spring of 1856, Lyell read a paper on the Introduction of species by Alfred Russel Wallace, a naturalist working in Borneo, and urged Darwin to publish his theory to establish precedence. Darwin pressed ahead despite illness, getting specimens and information from naturalists including Wallace and Asa Gray. In December 1857 as Darwin worked on his Natural Selection manuscript he received a letter from Wallace asking if it would delve into human origins. Sensitive to Lyell's fears, Darwin responded that "I think I shall avoid the whole subject, as so surrounded with prejudices, though I fully admit that it is the highest & most interesting problem for the naturalist". He encouraged Wallace's theorising, saying "without speculation there is no good & original observation", adding that "I go much further than you". Then on June 18, 1858, he received a paper from Wallace describing the evolutionary mechanism, with a request to send it on to Lyell. Darwin did so, shocked that he had been "forestalled" and though Wallace had not asked for publication, offering to send it to any journal that Wallace chose. He put matters in the hands of Lyell and Hooker, who agreed on a joint presentation at the Linnean Society on 1 July of On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection.

The initial announcement of the theory gained little immediate attention. It was mentioned briefly in a few small reviews, but to most people it seemed much the same as other varieties of evolutionary thought. For the next thirteen months Darwin struggled with ill health to produce an abstract of his "big book on species". Receiving constant encouragement from his scientific friends, Darwin finally finished his abstract and Lyell arranged to have it published by John Murray. The title was agreed as On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, and when the book went on sale to the trade on November 22, 1859, the stock of 1,250 copies was oversubscribed. At the time "Evolutionism" implied creation without divine intervention, and Darwin avoided using the words "evolution" or "evolve", though the book ends by stating that "endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved". The book only briefly alluded to the idea that man, too, would evolve in the same way as other organisms. Darwin wrote in deliberate understatement that "light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history".

Reaction

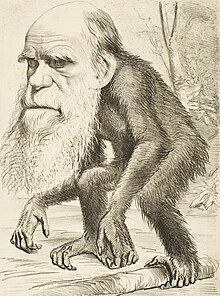

Darwin's book set off a public controversy which he monitored closely, keeping press cuttings of thousands of reviews, articles, satires, parodies and caricatures. Reviewers were quick to pick out the unstated implications of "men from monkeys", though a Unitarian review was favourable and The Times published a glowing review by Huxley which included swipes at Richard Owen, leader of the scientific establishment Huxley was trying to overthrow. Owen initially appeared neutral, but then wrote a review condemning the book. The Church of England scientific establishment reacted against the book, and Darwin's old Cambridge tutors Sedgwick and Henslow expressed their disappointment in him. Then Essays and Reviews by seven liberal Anglican theologians declared that miracles were irrational (and supported the Origin), distracting attention away from Darwin.

The most famous confrontation took place at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Oxford. Professor John William Draper made a boring speech on Darwin and social progress, then 'Soapy Sam' Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford, argued against Darwin. In the ensuing debate Thomas Huxley established himself as "Darwin's bulldog" – the fiercest defender of evolutionary theory on the Victorian stage. On being asked by Wilberforce whether he was descended from monkeys on his grandfather's side or his grandmother's side, Huxley apparently muttered to himself: "The Lord has delivered him into my hands" and replied that he "would rather be descended from an ape than from a cultivated man who used his gifts of culture and eloquence in the service of prejudice and falsehood" (there are several alternative versions of this story, see Wilberforce and Huxley: A Legendary Encounter). The story spread around the country: Huxley had said he would rather be an ape than a Bishop.

Many people felt that Darwin's view of nature destroyed the important distinction between man and beast. Darwin himself did not personally defend his theories in public, though he read eagerly about the continuing debates. He was frequently very ill, and mustered support through letters and correspondence. A core circle of scientific friends – Huxley, Charles Lyell, Joseph Dalton Hooker, and Asa Gray – actively pushed his work to the fore of the scientific and public stage, defending him against his many critics in this key scientific controversy of the era. Darwin's theory also resonated with various movements at the time and became a key fixture of popular culture. The book was translated into many languages and went through numerous reprints. It became a staple scientific text accessible both to a newly curious middle class and to "working men", hailed as the most controversial and discussed scientific book ever written.

Later life and death

Despite repeated bouts of illness during the last twenty-two years of his life Darwin pressed on with his work. He had published an abstract of his theory, but more controversial aspects of his "big book" were still incomplete; mankind's descent from earlier animals, and the mechanism of sexual selection which could explain features with no obvious utility other than decorative beauty as well as suggesting possible causes underlying the development of society and of human mental abilities. His experiments, research and writing continued.

When Darwin's daughter fell ill he set aside his experiments with seedlings and domestic animals to go with her to a seaside resort where he became interested in wild orchids. This developed into an innovative study of how their beautiful flowers served to control insect pollination and ensure cross fertilisation. As with the barnacles, homologous parts served different functions in different species. Back at home he lay on his sickbed in a room filled with experiments on climbing plants. He was visited by a reverent Ernst Haeckel who had spread the gospel of Darwinismus in Germany. Even at Cambridge, students now supported his ideas. Huxley gave "working-men's lectures" to widen the audience, and Wallace remained a supporter but increasingly turned to spiritualism. Variation grew to two huge volumes, forcing him to leave out man and sexual selection, but when printed was in huge demand.

New fossil evidence proved the antiquity of man, but other writers failed to fully tackle human evolution. Opponents claimed that the beauty of birds demonstrated divine guidance. These two subjects were tackled in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex which he followed up with The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Darwin produced practical explanations for the differences between males and females, and between different races and cultures. He also developed his ideas that the human mind and cultures were developed by natural and sexual selection, an approach which still persists in evolutionary psychology. His evolution-related experiments and investigations culminated in five books on plants, and then his last book returned to the effect worms have on soil levels.

Darwin died in Downe, Kent, England, on April 19, 1882. He had expected to be buried in St. Mary's churchyard at Downe, but at the request of Darwin's colleagues William Spottiswoode, President of the Royal Society, arranged for Darwin to be given a state funeral and buried in Westminster Abbey.

Religious views

Charles Darwin came from a Nonconformist background. Though several members of his family were Freethinkers, openly lacking conventional religious beliefs, he did not initially doubt the literal truth of the Bible. He attended a Church of England school, then at Cambridge studied Anglican theology to become a clergyman and was fully convinced by William Paley's teleological argument that design in nature proved the existence of God. However, his beliefs began to shift during his time on board HMS Beagle. He questioned what he saw—wondering, for example, at beautiful deep-ocean creatures created where no one could see them, and shuddering at the sight of a wasp paralysing caterpillars as live food for its eggs; he saw the latter as contradicting Paley's vision of beneficent design. While on the Beagle Darwin was quite orthodox and would quote the Bible as an authority on morality, but had come to see the history in the Old Testament as being false and untrustworthy.

Upon his return, he investigated transmutation of species, aware that his clerical naturalist friends thought this a bestial heresy undermining miraculous justifications for the social order, and aware that such revolutionary ideas were especially unwelcome at a time when the Church of England's established position was under attack from radical Dissenters and atheists. While secretly developing his theory of natural selection, Darwin even wrote of religion as a tribal survival strategy, though he still believed that God was the ultimate lawgiver. His belief continued to dwindle over the time, and with the death of his daughter Annie in 1851, Darwin finally lost all faith in Christianity. He continued to give support to the local church and help with parish work, but on Sundays would go for a walk while his family attended church.

In concluding his biography of his grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, Darwin recounted how after his death in 1802, false stories were circulated that he had called for Jesus on his deathbed, writing "Such was the state of Christian feeling in this country at the [time].... We may at least hope that nothing of the kind now prevails." Despite this hope, very similar stories were circulated following Darwin's own death, most prominently the "Lady Hope Story", published in 1915, claiming his sickbed conversion. Such stories have been heavily propagated by some Christian groups, to the extent of becoming urban legends, though the claims were refuted by Darwin's children and have been dismissed as false by historians.

Legacy

Charles Darwin's theory of evolution based upon natural selection changed the thinking of countless fields of study from biology to anthropology. His work established that "evolution" had occurred: not necessarily that it was by natural or sexual selection (this particular recognition would not become fully standard until the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's work in the early 20th century and the creation of the modern synthesis).

His work was extremely controversial at the time he published it and many during his time did not take it seriously. Darwin's theory of evolution was a significant blow to notions of divine creation and intelligent design prevalent in 19th-century science, specifically overturning the Creation biology doctrine of "Created kinds". The idea that there was no line to draw between man and beast would forever make Darwin a symbol of iconoclasm who removed humanity's privileged role in the centre of the universe. To some of his detractors, Darwin would be "the monkey man", often depicted as part ape.

Commemoration

During Darwin's lifetime many species and geographical features were given his name, including the Darwin Sound named by Robert FitzRoy after Darwin's prompt action saved them from being marooned, and the nearby Mount Darwin in the Andes celebrating Darwin's 25th birthday. In Australia's Northern Territory, the capital city (originally Palmerston) was renamed Darwin to commemorate the Beagle's 1839 visit there, and the territory now also boasts Charles Darwin University and Charles Darwin National Park.

The 14 species of Finches he researched in the Galápagos Islands are affectionately named "Darwin's Finches" in honour of his legacy. In 1964, Darwin College, Cambridge was founded, named in honour of the Darwin family, partially because they owned some of the land it was on. In 1992, Darwin was ranked #16 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history. Darwin was given particular recognition in 2000 when his image appeared on the Bank of England ten pound note, replacing Charles Dickens. His impressive and supposedly hard-to-forge beard was reportedly a contributing factor in this choice. Darwin came fourth in the 100 Greatest Britons poll sponsored by the BBC and voted for by the public.

As a humorous celebration of the theory of evolution, the annual Darwin Award is bestowed on individuals who "aid the process of evolution by demonstrating their unfitness" through fatally stupid actions.

Eugenics

Following Darwin's publication of the Origin his cousin Francis Galton applied the concepts to human society, producing ideas to promote "hereditary improvement" starting in 1865 and elaborated at length in 1869. In The Descent of Man Darwin agreed that Galton had demonstrated that "talent" and "genius" in humans were probably inherited, but thought that the social changes Galton proposed were too "utopian". Neither Galton nor Darwin supported government intervention and instead believed that, at most, heredity should be taken into consideration by people seeking potential mates. In 1883, after Darwin's death, Galton began calling his social philosophy Eugenics. In the twentieth century, eugenics movements gained popularity in a number of countries and became associated with reproduction control programmes such as compulsory sterilisation laws, then were stigmatised after their usage in the rhetoric of Nazi Germany in its goals of genetic "purity".

Social Darwinism

In 1944 the American historian Richard Hofstadter applied the term "Social Darwinism" to describe 19th- and 20th-century thinking developed from the ideas of Thomas Malthus and Herbert Spencer, which applied ideas of evolution and "survival of the fittest" to societies or nations competing for survival in a hostile world. These ideas became discredited by association with racism and imperialism. Though the term is anachronistic, in Darwin's day the difference between what was later called "Social Darwinism" and simple "Darwinism" was less clear. However, Darwin did not believe that his scientific theory mandated any particular theory of governance or social order.

The use of the phrase "Social Darwinism" to describe Malthus's ideas is particularly disingenuous, since Malthus died in 1834 before the inception of Darwin's theory was spurred by his reading the 6th edition of Malthus' famous Essay on a Principle of Population in 1838. Spencer's evolutionary "progressivism" and his social and political ideas were largely Malthusian, and his books on economics of 1851 and on evolution of 1855 predated Darwin's publication of the Origin in 1859.

Works

- Bibliography: Darwin Bibliography (including alternative editions, contributions to books & periodicals, correspondence & life)

- Works by Charles Darwin at Project Gutenberg

- Darwin Literature, Chapter-indexed, searchable versions of Darwin's works.

- Charles Darwin's Books in an easy to read format.

Published works

- 1836: A LETTER, Containing Remarks on the Moral State of TAHITI, NEW ZEALAND, &c. – BY CAPT. R. FITZROY AND C. DARWIN, ESQ. OF H.M.S. 'Beagle.' [1]

- 1839: Journal and Remarks (The Voyage of the Beagle)

- Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle: published between 1839 and 1843 in five volumes by various authors, Edited and superintended by Charles Darwin: information on two of the volumes –

- 1840: Part I. Fossil Mammalia, by Richard Owen (Darwin's introduction)

- 1839: Part II. Mammalia, by George R. Waterhouse (Darwin on habits and ranges)

- 1842: The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs [2]

- 1844: Geological Observations of Volcanic Islands [3], (French version)

- 1846: Geological Observations on South America [4]

- 1849: Geology from A Manual of scientific enquiry; prepared for the use of Her Majesty's Navy: and adapted for travellers in general., John F.W. Herschel ed. [5]

- 1851: A Monograph of the Sub-class Cirripedia, with Figures of all the Species. The Lepadidae; or, Pedunculated Cirripedes. [6]

- 1851: A Monograph on the Fossil Lepadidae; or, Pedunculated Cirripedes of Great Britain [7]

- 1854: A Monograph of the Sub-class Cirripedia, with Figures of all the Species. The Balanidae (or Sessile Cirripedes); the Verrucidae, etc. [8]

- 1854: A Monograph on the Fossil Balanidæ and Verrucidæ of Great Britain [9]

- 1858: On the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection

- 1859: On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life

- 1862: On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects [10]

- 1868: Variation of Plants and Animals Under Domestication (PDF format), Vol. 1, Vol. 2

- 1871: The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex

- 1872: The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals [11]

- 1875: Movement and Habits of Climbing Plants [12]

- 1875: Insectivorous Plants [13]

- 1876: The Effects of Cross and Self-Fertilisation in the Vegetable Kingdom [14]

- 1877: The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species [15]

- 1879: "Preface and 'a preliminary notice'" in Ernst Krause's Erasmus Darwin [16]

- 1880: The Power of Movement in Plants [17]

- 1881: Formation of vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms [18]

- 1887: Autobiography of Charles Darwin (Edited by his Son Francis Darwin) [19]

- 1958: Autobiography of Charles Darwin (Barlow, unexpurgated)

Letters

- Correspondence of Charles Darwin

- 1887: Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, ed. Francis Darwin Volume I, Volume II

- 1903: More Letters of Charles Darwin, ed. Francis Darwin and A.C. Seward Volume I, Volume II

References

- Charles Darwin, Voyage of the Beagle, (including Robert FitzRoy's Remarks with reference to the Deluge), (Penguin Books, London 1989) ISBN 0-14-043268-X

- E. Janet Browne, Charles Darwin: Voyaging and The Power of Place (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995-2002).

- Adrian Desmond and James Moore, Darwin (London: Michael Joseph, the Penguin Group, 1991). ISBN 0-7181-3430-3

- The Darwin Deathbed Conversion Question

- Richard Keynes, Fossils, Finches and Fuegians: Charles Darwin's Adventures and Discoveries on the Beagle, 1832-1836. ( London: HarperCollins, 2002).

- James Moore and Adrian Desmond, "Introduction", in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (London: Penguin Classics, 2004). (Detailed history of Darwin's views on race, sex, and class)

- Diane B. Paul, "Darwin, social Darwinism and eugenics," in Jonathan Hodge and Gregory Radick, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Darwin (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 214-239.

External links

- Charles Darwin biography at the Natural History Museum, London

- AboutDarwin.com

- The Friends of Charles Darwin

- Darwin's portrait on the £10 note

- Twelve different portraits of Charles Darwin at the National Portrait Gallery, U.K.

- BBC News: "Darwin family repeat flower count"

- Examine Darwin's crustacean collection online

- A short biography of Darwin